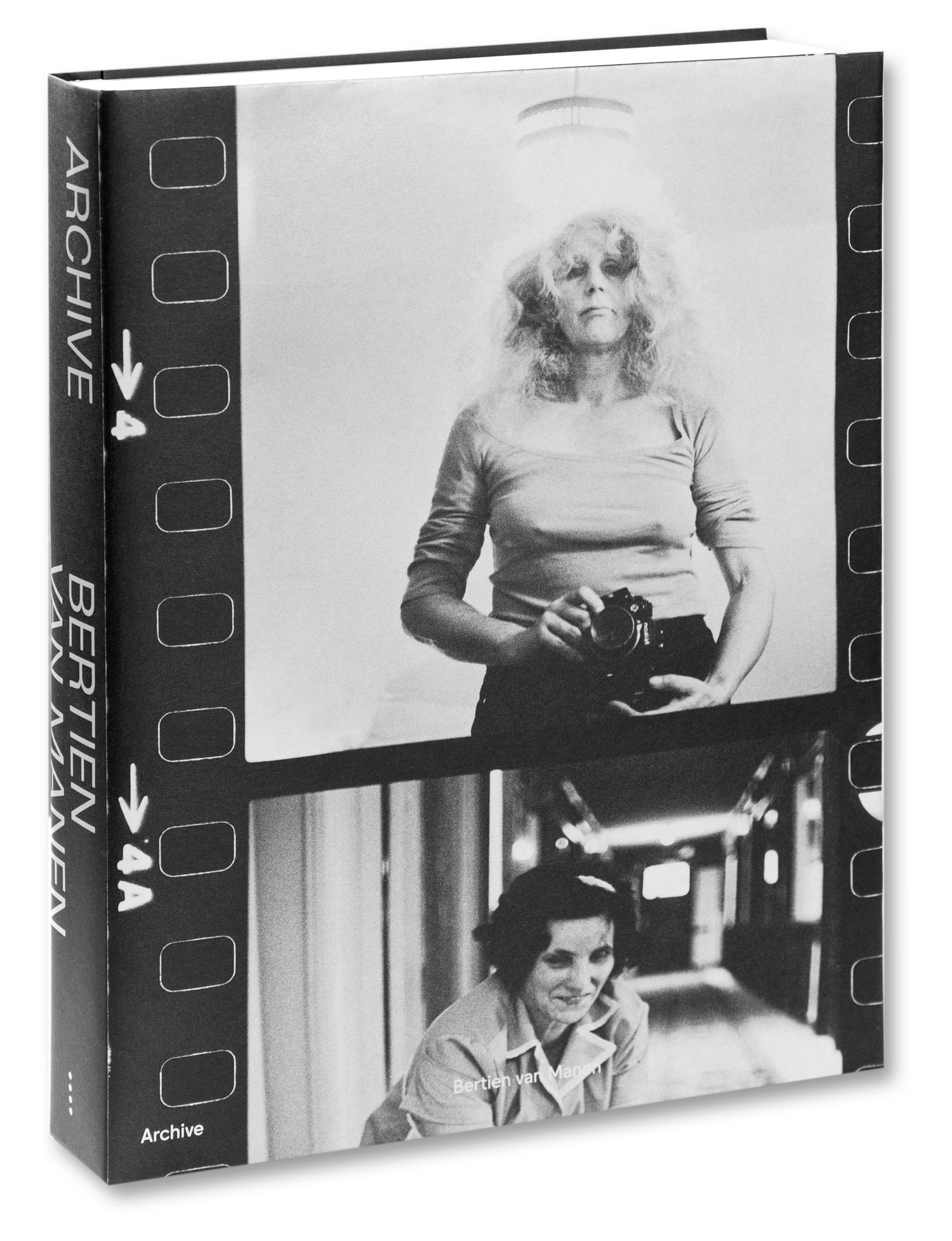

On the cover of Bertien van Manen’s Archive a woman, bold and braless, meets our gaze, her unruly hair haloed by overhead light. She seems fierce (in the Irish sense; wild, strong), holding an SLR camera at her belly. This self-portrait, and the cover’s bottom third showing a smiling hotel maid, who could be recollecting a loving moment, or laughing at a joke to which we cannot be privy, spotlight van Manen’s gift: her loose, raw capturing of the commonplace, her illumination of the divine in the everyday.

Three salient facts about her: Van Manen was born in The Hague in 1942 and the Dutch directness and aversion to frippery is evident in her portrayal of the familiar, messy, intimate details of everyday life. She suffered through seven years at Sacred Heart, an elite Catholic boarding school. As a young wife and mother discovering photography in the seminal ’70s—a seminal decade for the medium—van Manen struggled to claim the agency to make her own way.

Since then, she has honed her gift for transferring the familial trust and intimacy of her own ‘Home’ chapter images in Archive, the playful, exquisite pleasures of what a loving family shares and the aching punctum of its eventual loss, to her subjects. Van Manen’s empathetic, embedded rapport moves beyond a temporary, egalitarian footing into decades-long relationships. She seeks out migrant women and women miners, and sleeps in her subjects’ trailers in Appalachia, in rural Chinese shacks, in places minus basic amenities. “Shared space with a subject is just how I work as a woman and a photographer. I photograph them, I think, from the inside out,” she explains.

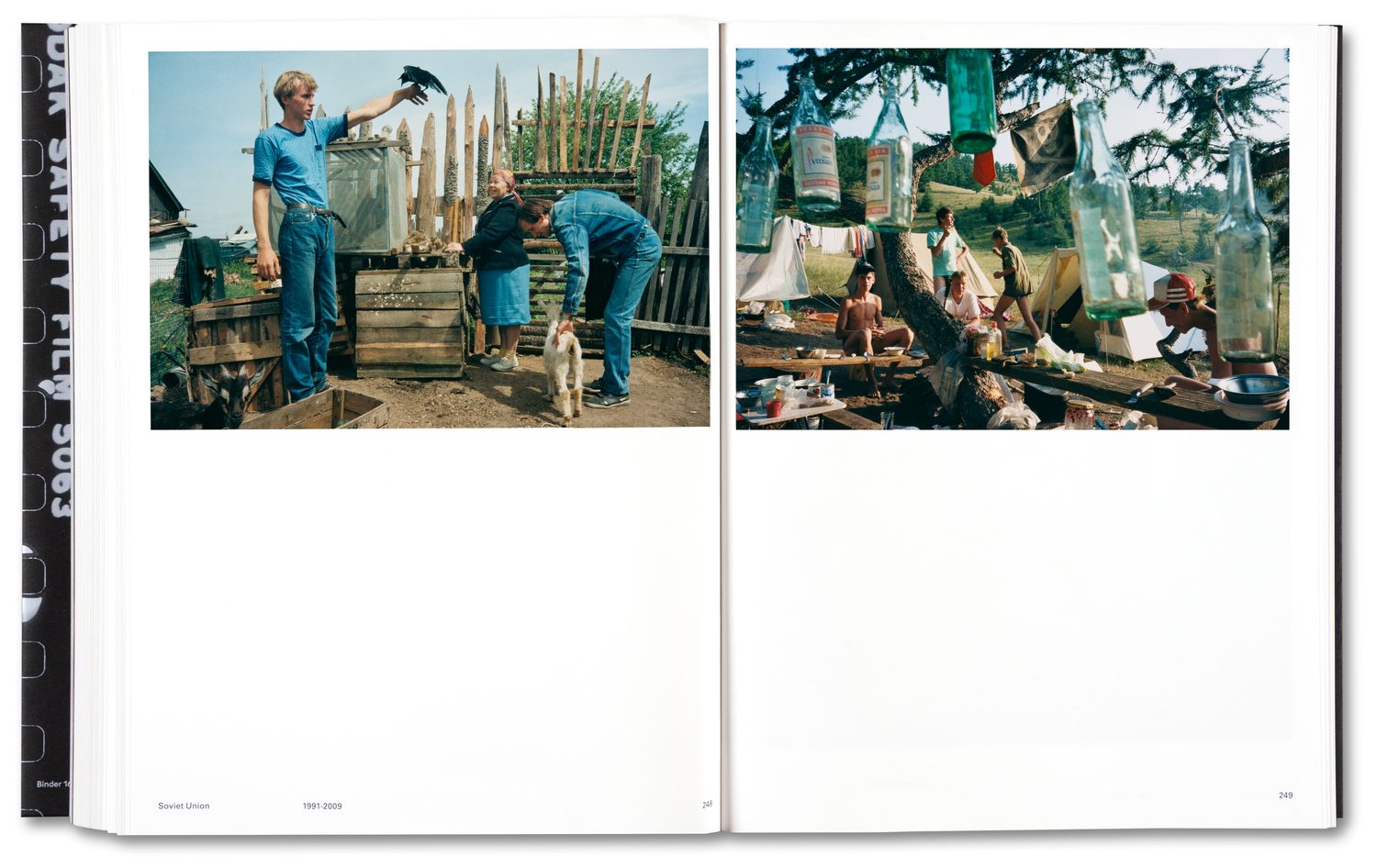

In terms of her aesthetic approach, van Manen sidesteps clichés and sentimental assumptions in informal, off kilter compositions, the physical chatter of parents and kids, bodies and babies jumbled together, tumbling out of the frame. Complex, seismic historical shifts are encapsulated in these compositions, such as the opening up of China to western culture at the cusp of the 21st century, rendered to a human scale in a shot of the tiny private space a young woman occupies. Other regions in the midst of major change and countries on the cusp of independence are reflected through images of migrant families in Amsterdam; Appalachia and Romania.

There is an element of van Manen’s work that fulfills a vocation, a calling, driven by a lifelong need to be industrious. Only people raised Catholic, van Manen observes, understand the residue of the relentless voice within your head, the guilt. One never spits out the host. “I always feel guilty reading newspapers or a book. I should do something serious. I always have this guilty feeling to be of use.” Yet from that experience, van Manen gives us the essence of a life of spiritual contemplation, capturing a nun covering her face with her hands, at the intensity of which van Manen marvels, “She does nothing but pray, in silence, all day.”

But as a consequence of that lingering guilt she also lost the capturing of a seminal moment. Forbidden by the priest of a Central Russian Orthodox church to photograph their celebration of a convent’s Sunday evening’s prayers, van Manen sneaks in anyway and crouches down on her knees, “not to confess but to capture this biblical—and to me apocalyptical—image of self-humiliation,” she writes in a journal entry. Positioning her shot, she is “paralyzed by an inexplicable fear…still fearful of the authority of the church and its unfathomable, obscure powers.” We can feel her pain as “beautiful shots pass, one after another, as they dissolve into oblivion.” Her disappointment, the prohibition “on my desire, I could imagine the photos, it said something to me about the sacrifice and humility of women in the Roman Catholic church, 33 of them prostrating themselves to this priest and the power he held over them.”

It was in the photographs of Robert Frank that she discovered an opposite kind of power. Describing his work as “honest, free, and unpretentious,” Frank’s vision was pivotal for van Manen’s own evolution, shaping her signature spontaneity in capturing the casual moment. While he revered Walker Evans, Frank’s ‘snapshot aesthetic’ unharnessed documentary photography from both its formal preciousness—Evans’ objectivity and precise composition—and its timeline. Jack Kerouac’s observation that Frank “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film,” applies to van Manen’s work; like Frank’s, both poignant and poetic, raw and timeless.

Van Manen’s own sense of liberation was hard earned. Since 1839, when Daguerre was credited with the invention of photography on the heels of the 1848 Seneca Falls first women’s rights convention, the use of photography as an instrument to record their forays and passages, both personal and public, has had an impact on women’s evolving freedom. As a daughter, mother, wife, van Manen’s struggles came at no small price. Her family did not understand this impulse to make pictures, except for her father who imprinted his belief in her by purchasing a rubber stamp for her earliest photos, validating her as an image maker, in contrast to her mother’s emphasis on being “a beautiful woman and perfect mother.”

“I had been brought up Roman Catholic. I had to really fight to be able to do what I did, to travel, to create something. I didn’t have a choice,” she adds. “I wanted to make something for the world.” She corrects herself, feeling that perhaps this statement is grandiose.

Van Manen shares Frank’s modesty as well as unapologetic stance, and an unrelenting declarative insistence on a sense of authenticity that has become increasingly elusive. That reticence to self-importance recalls Frank’s words about Evans: “I thought of something Malraux wrote: ‘to transform destiny into awareness.’ One is embarrassed to want so much of oneself.” For van Manen, perhaps this is a calling in its purest sense, unburdened by the religious.

Archive comes on the heels of van Manen’s 2020 solo exhibition at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, which was brilliantly contextualized with the work of other photographers thanks to curator Hripsimé Visser. Her monograph profile of van Manen is a testament to a lifetime of work in so many places—Europe, America, China and the former Soviet Union—advancing an empathetic, vernacular approach to documentary photography, as well as her resilience and bravery.

Journeying through her rich career, the book also charts the subtle changes in van Manen’s approach to photography, shaped by her own life experience. She began using automatic compact cameras by the late 1980s and in the last chapter, a cheap analog snapshot that abstractly renders western Ireland marks a departure from her earlier work. “I came to look for my husband after his death… I just wanted to find him somewhere in the Atlantic and I made all these pictures of the sea. This is the one that I like the most,” she explains. “But I did not find him. It was an illusion, a dream.”

She adds, “I like to stay enigmatic; sometimes you don’t know what I want to say there. It looks very silent and peaceful but there’s so much going on underneath.” Along with the way in which this image of the sea represents the symbolic and secret, van Manen also feels it references the Irish writer Sally Rooney’s characterization of the unease and fragile state of contemporary lives, a fearfulness lurking under a placid surface. “I found more but I mean, it’s in the pictures…” she says. And in these blurry, abstract takes of moon and waves, a washed-up jellyfish and a dead lamb with its bloody innards exposed, mainly devoid of people—outside of a few figures, distanced from each other, wandering on the coast—one cannot hear a plangent slap of waves but the viscerality of the images, like death, is irreversible.

There is a double portrait of van Manen where that surface seems shattered. She is sitting on her husband’s bed a month before he died and they are listening to Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Her husband took the two photographs. “You can see,” she says, “that in the lower photo I am crying.”

Engaging with Archive is an immensely pleasurable physical experience, haptic in its tactility and texture, soft cover and the ink-absorbing paper that van Manen began using with the first of her ten books, A hundred summers, a hundred winters, published in 1994. Describing her preference for books over exhibitions she notes that, “You can hold them in your hands, have them in your house. You can smell them, the paper, the physical object. An exhibition is ephemeral.” Noted book designer Hans Gremmen’s responsive translation of van Manen’s signature loose intimacy is seamless, and her journal texts illuminate the images on another level. One of her favorite photos is from this book: a woman waiting for hours in a former Soviet Union railway station, curled up under a large window brimming with a snowy vista. The title A hundred summers a hundred winters is a Russian greeting to friends not seen for a long while.

Part of the allure of a book like Archive is how it fulfills the aesthetics of an art object and the intimate relationship one can develop with such objects. Picking up this book, whether for the first or hundredth time, feels like visiting an old and very dear friend.