For the past month, anti-Trump super PAC the Lincoln Project –– which promised to bridge America's divides by bringing dignity back to the Republican Party –– has been put through the wringer and hung out to dry. First, allegations of sexual harassment by more than twenty people, including two minors, against Lincoln Project co-founder John Weaver came to light in late January. According to various reports, several of the group's prominent Republican founders knew about the allegations as early as March of 2020, yet no subsequent investigations were ever launched. Two weeks later, it was revealed that over two-thirds of the $90 million raised by the Lincoln Project was paid to firms run by the group's founders, leaving only $27 million spent on the ad campaign in support of congressional Democrats and against Donald Trump it promised to run.

Additional allegations have since accused the Lincoln Project leaders of cultivating a toxic workplace rife with infighting, sexism, and homophobia. The Lincoln Project's co-founders, Steve Schmitt and Jennifer Horn, as well as its senior advisor, Kurt Bardella, have resigned amid the turmoil, throwing the group into a chaotic state of disunity.

It's easy to dismiss the organization's dissolution as a failure of workplace ethics or compliance, but let us not forget: the Lincoln Project was also a failure of political strategy.

Not only did highly-moneyed liberals rally behind a Republican-backed organization that now appears foundationally rotten; they did so because they erroneously believed its strategy to be new and bold. According to Federal Election Commission filings, here are some of the Lincoln Project's biggest donors:

- Democratic dark money group Majority Forward ($1.35 million)

- Democratic dark money group Sixteen Thirty Fund ($300,000)

- Hedge fund manager Stephen Mendel Jr. ($1 million)

- Oil heir Gordon Getty ($1 million)

- Media magnate David Geffen ($500,000)

- Bain Capital Co-Chair Joshua Bekenstein ($100,000)

- Founder of Dreamworks Pictures Jeffrey Katzenberg ($100,000)

- Philanthropist Liz Lefkofsky ($100,000)

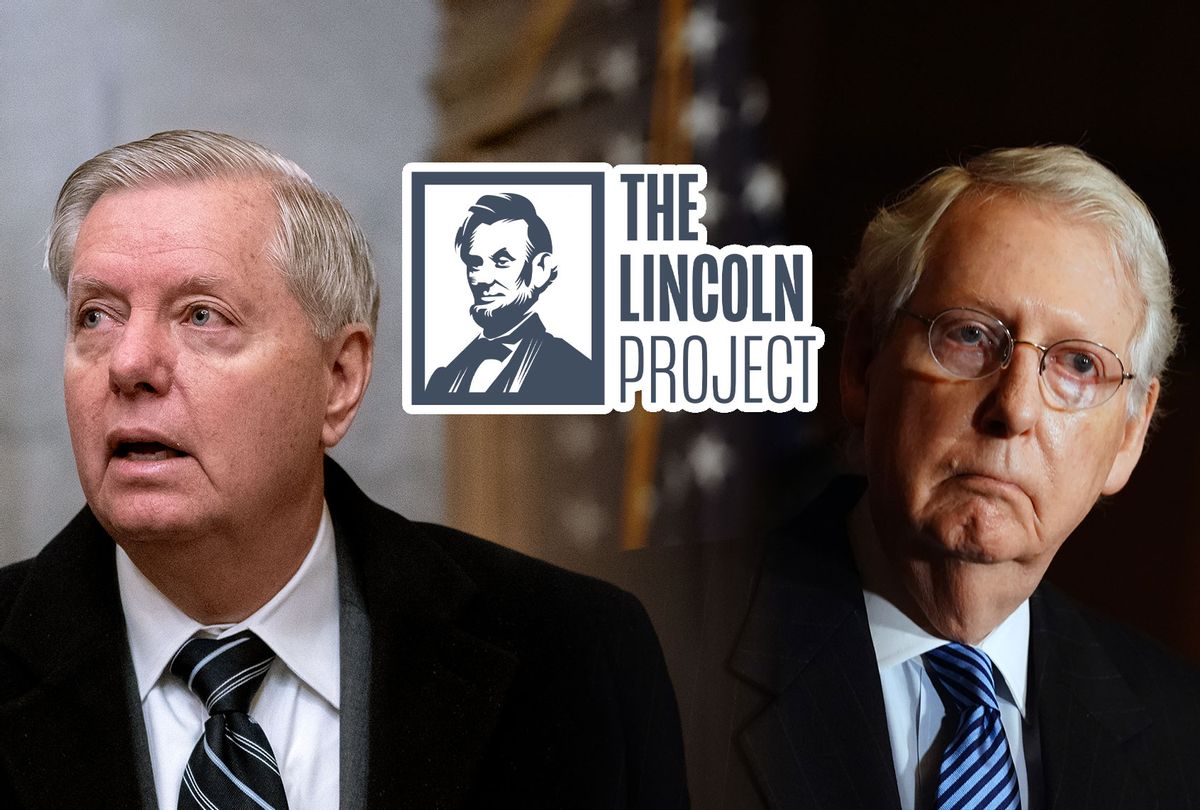

Even with such support from big-moneyed liberals, however, it's not readily apparent that the Lincoln Project did much of anything to help Democrats. More Americans voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 election than they did in 2016, after all. Democrats also overwhelmingly lost state legislatures throughout the country. Despite all of the Lincoln Project's sensationalized broadsides against key Trump's congressional allies, the group also failed to weed out any of the most corrosive figures within the GOP, such as Senators Mitch McConnell, R-KY, Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., Ted Cruz, R-TX, or even Maine's Susan Collins.

Amid the big Democratic disappointment in 2020, however, there was one election that stood apart from the rest: Georgia's election of Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock to the Senate. Not only did their runoff victories over Republican incumbents David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler, respectively, bring the Senate to an even split, with Vice President Kamala Harris as the designated tiebreaker, it re-introduced America to a strikingly quaint way of winning elections: organizing.

Ossoff and Warnock both heavily relied on a Democratic organizing project that had actually preceded their bids for office and had built up the state's political infrastructure through community-driven efforts for over a decade. The project's co-founder, Stacey Abrams, has since been hailed for helping to flip Georgia blue, but it is instructive to compare her victory with the Lincoln Project's failures.

Abrams was elected to the Georgia State House of Representatives in 2007, eventually climbing her way to minority leader in 2011. In 2014, dead set on flipping Georgia politically in tandem with its changing demographics, Abrams founded the New Georgia Project and the Voter Access Institute, two grassroots, working class-led organizations that seek to expand voting registration in communities of color.

During her bid for governor in 2018, Abrams partnered with a vast ecosystem of political and non-profit organizations and emphasized the need to personally engage with voters through continued groundwork rather than swaying them with rancorous attack ads with titles like "Blood", "Oath," or "Bounty" for a few months during an election year. Abrams also defied conventional political wisdom by targeting non-voting Georgians of color as opposed to appealing only to registered voters. As she told The New York Times Magazine, "Our innovation was that [non-voters] could count, and we saw there were a lot of folks who simply wanted someone to invest in them."

After Abrams lost to her Republican gubernatorial opponent, Brian Kemp, who eked out a 55,000-vote win out of 4 million cast in 2018, she founded Fair Fight, a national voting rights organization that worked to educate voters and provide resources for them to engage in the electoral process during the 2020 election.

"We're going to train folks to protect the right to vote, to assure every ballot gets counted, to make sure there's a hotline in each state so that when the new law shows up people know what they need to do," Abrams said in speech to the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades, explaining her strategy of informing Georgia's electorate. "We're going to have a fair fight in 2020 because my mission is to make certain that no one has to go through in 2020 what we went through in 2018."

It was during this period that a wide array of social justice organizations based in Georgia, predominantly led by women of color, worked in conjunction with Abrams to push the Peach State blue. For example, ProGeorgia, a coalition of over thirty non-profit organizations promoting civic engagement, acted as a hub for various community interests. Other groups like SONG Power and Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR) that led outreach programs for the Biden campaign continued their efforts through the Georgia runoffs. According to In These Times, SONG Power and GLAHR managed to knock on 150,000 doors all across Georgia during the summer. By the end of the 2020 election cycle, 800,000 new voters had registered in the state, forty-nine percent of whom were people of color. The increase made for a record turnout of more than four million voters.

Although Abrams' political project benefited from a large pot of grassroots donations, she avoided giving money to specific candidates, instead building out the political infrastructure needed to amass broad support for progressive policies. Needless to say, the remarkable success of her project presents an important question for Democratic donors: Will they continue to bankroll short-term avenues of influence that focus on the success (or failure) of individual political candidates? Or will Democrats finally focus on enfranchising new voters and establishing a broader, longer-term coalition of support? Given how the 2020 election cycle played out, it appears that the latter strategy has more political potential.

According to a study conducted by Democratic super PAC Priorities USA which examined the effects of the Lincoln Project's ads on swing voters, the better an ad performed on Twitter, the less likely it was to persuade voters. "The underlying mechanism of persuasion, I think of it like cough medicine," said Nick Ahamed, Priorities' analytics director, "People don't enjoy having their mind changed."

In fact, political advertising in general –– particularly for primary and general elections –– may be far less effective than its backers might have you believe. A study produced by scientific journal Science Advances found that ads of all kinds, in fact, had no virtually no effect on a candidate's favorability. "Positive ads work no better than attack ads," said coauthor of the study Alexander Coppock, an assistant professor of political science at Yale. "Republicans, Democrats, and independents respond to ads similarly. Ads aired in battleground states aren't substantially more effective than those broadcast in non-swing states."

Yet Democrats have not begun to think about curbing ad expenditures. Out of the $6.9 billion budget Democrats spent on campaigning for the 2020 election, $600 million went to TV ads alone. (This excludes digital ads, print ads, radio, etc.) Imagine the kind of voter turnout Democrats would yield if they spent $600 million every couple years on building a more robust political infrastructure. It behooves Democrats –– and particularly high-net worth liberals in this case –– to think about how they will win elections over beyond the scope of one administration. Because, as evidenced by Trump's personal vendetta against President Obama's legacy, one election is simply not enough.

If there's anything liberals have learned from Donald Trump's election and everlong forever-years in the Oval Office, it's that Trump's ascendancy was not random; it was a product white working-class voters feeling increasingly disenfranchised by an economy that did not serve them. Democrats may have come to terms with this. But they have not reckoned with its broader implication: you cannot consistently win elections unless you consistently support those who vote in them.

Shares