Foreign dynasty's rise to power in ancient Egypt was an inside job

The Hyksos once ruled Egypt, but they didn't arrive as invaders.

A mysterious dynasty of foreigners may not have invaded and taken control of ancient Egypt as was long thought. Rather, the ethnic group known as the Hyksos seems to have seized power from within Egypt.

The Hyksos ruled Egypt from 1638 B.C. to 1530 B.C. But the new study, which involved chemical analyses of teeth collected from Hyksos cemeteries, suggests that this ethnic group thrived in Egypt for generations.

Though the Hyksos were the first foreigners to rule ancient Egypt, written records of their reign are scant. For hundreds of years, the only known mention of the Hyksos was in the Greek tome "Aegyptiaca," or "History of Egypt," written by a Ptolemaic priest named Manetho who lived in the early third century B.C. and who chronicled the rule of the pharaohs.

Related: Image gallery: Female Egyptian mummy discovered

According to Manetho, the Hyksos made their move after the end of Egypt's Middle Kingdom, which crumbled around 1650 B.C. During a time when Egypt was in turmoil, Hyksos leaders purportedly led an invading army "sweeping in from the northeast and conquering the northeastern Nile Delta," researchers wrote in a new study, published online today (July 15) in the journal PLOS One.

Deciphered hieroglyphics later provided historians with a little more detail about the alleged Hyksos coup, but accounts of this dynasty remained biased and incomplete. Egyptian rulers frequently destroyed records or spread propaganda about their predecessors, and the Hyksos people were linked to "disorder and chaos" by the dynasties that succeeded them, according to the study.

Non-Egyptian customs

In 1885, archaeologists uncovered ruins of the Hyksos capital, the city of Avaris, at a site on the Nile Delta called Tell el-Dab'a, about 75 miles (120 kilometers) north of Cairo. Decades of excavation followed; architectural details and cultural artifacts found in cemeteries, temples and residences hinted that the Hyksos originated in the Near East, said lead study author Chris Stantis, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at Bournemouth University in Poole, England.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

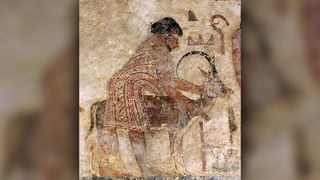

"The tombs with non-Egyptian burial customs were especially intriguing — typically males buried with bronze weaponry in constructed tombs, without scarabs or other protective amulets like Egyptians would have been buried with," Stantis told Live Science in an email.

"The most elite had equids of some sort (potentially donkeys) buried outside the tombs, often in pairs as though ready to pull a chariot. This is both a foreign characteristic of burial style, but also suggestive of someone [with] very high status," Stantis said.

But long before the Hyksos emerged as a ruling dynasty in 1638 B.C., waves of migration brought this ethnic group into Egypt's delta region, the scientists reported in the study.

Migration of women

Stantis and her co-authors collected enamel samples from the teeth of 75 ancient people in three locations at Tell el-Dab'a. They scrutinized the enamel for strontium isotopes (variations of an element), and then compared the ratios with isotopes preserved in other remains and artifacts from the region and along the Nile, to determine whether the people living in Tell el-Dab'a were "local."

"Strontium enters our bodies primarily through the food we eat," Stantis said. "It readily replaces calcium, as it's a similar atomic radius. This is the same way lead enters our skeletal system; although, while lead is dangerous, strontium is not."

Because strontium reflects the underlying geology of a region, and because dental enamel geochemistry takes shape early in life, individuals with enamel values that match local values are thereby considered to be local to the region, Stantis explained.

Related: Peaceful funerary garden honored Egypt's dead (photos)

The scientists also used geochemical analysis to determine the sex of the individuals, to better understand the male-to-female ratio in the Hyksos capital.

Isotopes in the majority of the teeth — belonging to 36 individuals — identified them as settling in Egypt prior to the start of the Hyskos dynasty, contradicting the narrative that the Hyksos first appeared as an invasive army. Intriguingly, the wide range of isotope values hinted that immigrants "did not come from one unified homeland," representing "an extensive variety of origins," according to the study.

Chemical analysis of the teeth also revealed that 30 of the individuals were female, while only 20 were found to be male. If the Hyksos had appeared in Egypt as invaders, the first wave of Hyksos would likely be all male, because men were typicallythe fighters in ancient societies. By comparison, the large number of women "immigrants" pre-dating the Hyksos dynasty suggests that women were at the forefront of the Hyksos migration to Egypt, the researchers reported.

"Some previous research talked about men moving into Egypt: shipbuilders, merchants, mercenaries. The concept of women moving, as a family or possibly alone, hasn't really been discussed," Stantis explained.

"We need to look more into who these women were and why they moved, but the fact that there's more women than men changes a lot of interpretations."

With a clearer picture of when the Hyksos arrived and how they settled in Egypt, the next steps will involve piecing together how the Hyksos adapted to the customs of their new home and how they blended new practices with their own cultural traditions, Stantis said.

"Are the individuals buried in the Near Eastern styles first-generation immigrants, or are they continuing their ancestral funerary customs despite being born and raised in the Delta?" she said. "Dietary isotopes would also let us think about whether nonlocals were eating significantly different foods from locals, or if they shifted quickly to Egyptian food customs."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular