Tiny, Ancient Native American Weapons May Have Been Used to Train Children to Fight

In ancient times, some Native American groups taught their children how to fight and hunt using miniature versions of popular projectile weapons, according to a new study.

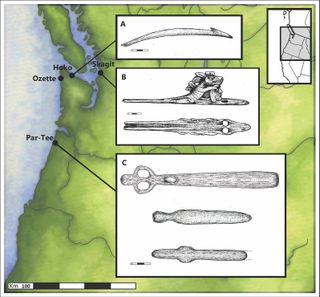

Over a thousand years ago, Chinookan- and Salish-speaking Native Americans lived on the northern Oregon coast near the mouth of the Columbia River, where they ate seafood and crafted tools and weapons. In the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists excavated this area, known as the Par-Tee shell midden site, which is filled with heaps of seashells and various deposits lumped into a pile called a midden. These previous finds included burials, hearths and about 7,000 tools, but most of those artifacts remain unanalyzed, according to a statement.

In this new study, a group of researchers examined over 90 of these previously unanalyzed artifacts that are fragments of an ancient weapon called an "atlatl."

Related: Photos: Ancient Arrows from Reindeer Hunters Found in Norway

Predating the bow and arrow, the atlatl was a dart-throwing weapon that could launch projectiles with great force. Made from whalebones, it had a grip on one end and a hook for a dart on the other. The weapon was key to these groups' survival, and people who knew how to use them had significant advantages.

"The ability to operate such weapons effectively was a critical skill, but not a simple one to master," the researchers wrote in a new study, published Dec. 10 in the journal Antiquity. "Proficient atlatl users probably would have had greater success in hunting than those less skilled with the atlatl, resulting in dietary and social advantages for themselves and their community."

What's more, people who could effectively use the weapon were likely more successful in warfare and self-defense, the researchers added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team found that the weapons, particularly the grips, varied greatly in size; the largest was 166% larger than the smallest. Because a person's sex, body mass and height account for only 10% to 15% in the difference of the size of an adult human palm, the researchers concluded that the small weapons were used to train children.

"Basically, they scaled down their atlatls so they were more easily usable in small hands," lead author Robert Losey, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta, said in the statement. In this way, children were taught how to use and master the weapons, he added.

These smaller weapons likely were not models or toys but actually worked as weapons; previous experiments found that such weapons could hurl a dart around 98 feet (30 meters), according to the statement. Compared with other sites on the West Coast of North America, Par-Tee boasts an "unusually high" abundance of these weapons, the authors wrote in the study. It's unclear why, but most other atlatls were likely made from wood, as opposed to whalebone, and thus didn't survive to this day, they wrote.

"The Par-Tee atlatls were made during what appear to have been the last few centuries of the widespread use of these weapons on the northern Oregon Coast," the authors wrote. They might have even been used alongside the "newly introduced bow and arrow."

- Photos: Ancient Burial of Elite Members of Nomadic Tribe

- Centuries of Tradition: Stunning Photos of Native American Hopi Pottery

- In Photos: Discoveries at the Site of the Pequot War in Connecticut

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular