The most compelling speculative fiction takes something about the world as it exists and alters it in such a way that the familiar is made into something provocative. This disruption of the familiar lies at the heart of the best speculative fiction.

America at present is already a surreal nightmare. A mentally unwell ignorant violent racist sexist greedy and cruel reality TV show host is president. He leads a political cult. Christian Nationalists and Christian Dominionists want to transform the United States into a "biblically correct" society in violation of the United States Constitution and its guiding principle that church and the state should be separate. And Donald Trump, a proud and resplendent sinner, is viewed by right-wing Christians as god's prophet and their savior. And the so-called resistance and other people of conscience are still struggling to create a cohesive and coordinated movement to oppose American fascism as birthed by Donald Trump's adminstration.

Michael Pence — Trump's vice president — is a Christian Fascist who does his movement's bidding as he and the Republican Party work to overturn women's reproductive rights and freedoms as part of an overall assault on human rights and human dignity in America and around the world. Pence and the Christian Right's obsessions with supposedly "protecting the unborn" and "living the principles of Jesus Christ" (their distorted version of him) does not extend to having any empathy or sympathy for the brown and black babies, children, and adults being held in Trump's concentration camps and otherwise terrorized by Trump's regime.

The corporation increasingly has power which rivals if not surpasses the nation-state. New technologies are radically altering the labor market and how people make sense of and perform their own identities. For example: the algorithm distributes resources and shapes individual's desires, wants and life chances — all the while it remains invisible to most people. The American people are amusing themselves to death in a society where there are very high levels of loneliness but they are also "hyper-connected" to one another online. In total, the American people are under constant surveillance by corporations and the state. But most Americans do this willingly through participatory totalitarianism.

Director and screenwriter Darcy Van Poelgeest's powerful new graphic novel series "Little Bird' (from publisher Image Comics) is some version of this present day America and its malignant reality projected forward into the future.

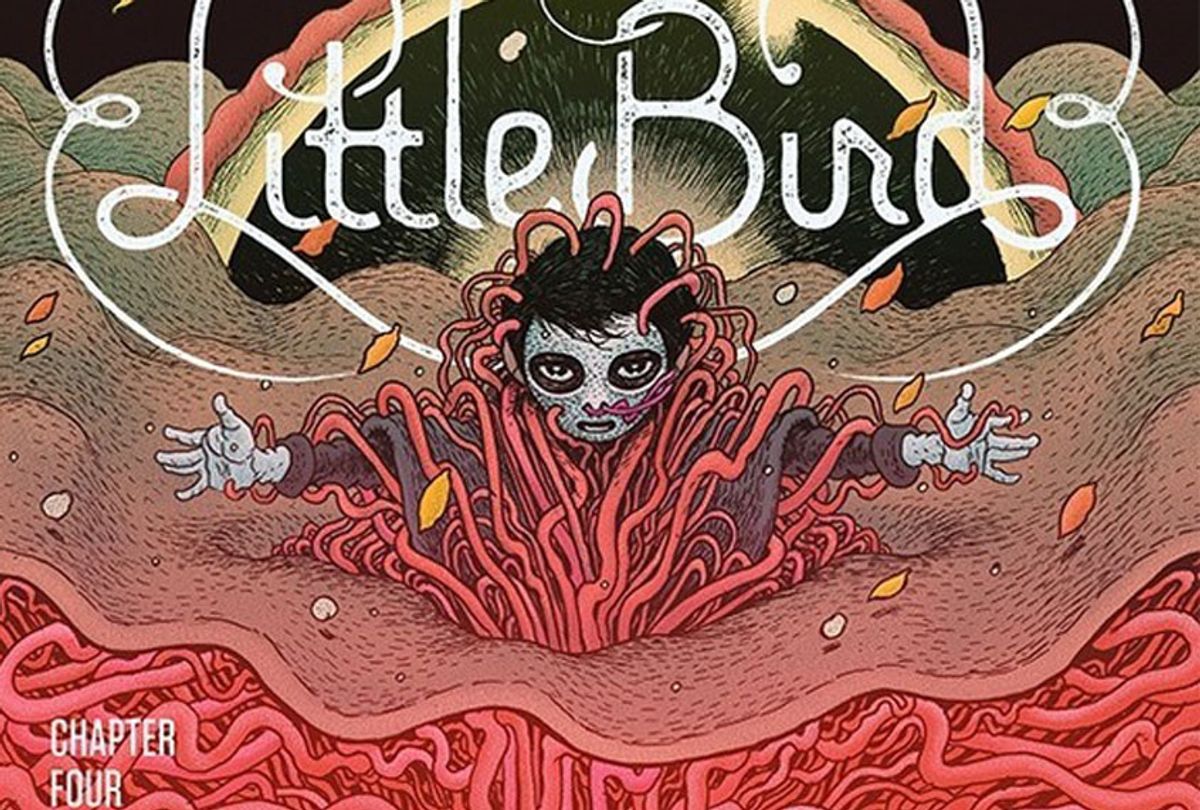

"Little Bird" (with art by Ian Bertram and colors by Matt Hollingsworth) tells the story of a Christian nationalist America led by the religious zealot "Bishop" who rules from the "New Vatican" in a decades-long war of conquest against Canada.

Poelgeest's story is one of family, human dignity and resistance against oppressive power as shown through the coming of age story of the titular character and hero Little Bird, a 12-year-old girl and member of the First Nations who is trying to inspire the Canadian Resistance to fight on in its freedom struggle against the conquering American forces.

In my recent conversation with Darcy Van Poelgeest, we discussed the origins of "Little Bird," the ways that it is a meditation on resistance and human dignity, and what it is like to watch America lose its way from the hope of the Obama years to the terror and cruelty of Donald Trump.

Poelgeest also explains how even history's great villains such as Donald Trump actually believe that they are doing the right thing. In this conversation, Poelgeest also shares how the humanity of "Little Bird" channels what he learned from his mother's political activism and the bravery of his Dutch grandparents during World War 2.

"Little Bird" #5, the final issue of the series, was released last week. "Little Bird" will be available in a collected edition at a future date.

This conversation has been edited for clarity.

"Little Bird" is such a confident story. There is no regret or second guessing in the story. Because of that "Little Bird" is also very efficient. There is not a lot of exposition. You and your co-creators present the world simply as it exists and on its own terms. That is a very bold choice. How did you decide to proceed that way?

I have a great amount of respect for the readers and I think that is where my confidence comes from. I write for them. I am creating stories the way that I would like stories to be told to me.

In many ways I suppose I am doing it for myself. I feel like some writers do not have that much faith in their readers. I don't understand this. At several of the signings for "Little Bird" that I have done people come up to me and we chat. They understand the story. I love that. They are getting the details and the subtext. I would rather rather risk the reader being challenged than just flipping through the pages and not having to think.

Where did that respect come from? This commitment to the truth of the story?

Long before you are a storyteller you are a story receiver. It always irritated me when I watched a movie or read a book — or any other type of entertainment for that matter — and I feel like it is being spoon-fed to me. It is not a nice feeling. Moreover, that means the story is not as engaging because by being challenged by a story we become part of it. We become invested in such a way that we are part of the story. We are made part of the process of telling that story. When everything is given to us by a story, even if it's done in an exciting way, there is still that barrier.

Of course "Little Bird" reflects the angst — as well as hope — of this present moment of political and social tumult across the West and really in many ways around the world. When did you decide to write "Little Bird"?

In my first documentary project I interviewed indigenous youth who were incarcerated. I found myself in this jail for several days talking to young indigenous youth who had gotten in trouble with the law in some pretty bad ways. This was really an awakening to me regarding many of the challenges that the First Nations indigenous community in Canada are facing, specifically in British Columbia. This project gave me a very different perspective on their experiences and struggles. In the same project I also interviewed indigenous elders about the legacy of the residential school system here, the lasting impacts of that, most specifically on children being separated from their families.

As I continued to develop a relationship with the First Nations communities this became very important to me. More people need to understand these struggles and triumphs.

In "Little Bird" I do this by focusing on a young indigenous girl in a science fiction setting. And then of course while I was writing "Little Bird" Barack Obama was still president. I found his whole presidency very inspiring. But if you live long enough one gets to see the pendulum swings backward. So then I started wondering what happens after Barack Obama and that hopeful moment. When the pendulum swings back, how far does it go now?

You are a Canadian. What does the United States in this moment look like from afar?

It does not look good. "Little Bird" is quite far-fetched — but it looks a little less so far-fetched every day with Donald Trump being president. This is all very scary.

There is a hard truth that many people do not want to look at: We are all flawed, and in general, people are working from an honest place. That is a tough fact to accept for most. As much as I dislike Donald Trump, I do not believe that he wakes up in the morning and says to himself, "how can I make the world worse?" Donald Trump actually believes that what he is doing is good. Now how do we define "good"? What he is doing is mostly good for him and he obviously does not possess much empathy, but I think Trump thinks he is also doing good things for other people as well.

The character Bishop is a Christian Nationalist who leads this future United States in a holy war against Canada. There is a speech in "Little Bird" which sounds like it could have been delivered by Michael Pence or any other Christian Fascist. Despite being the aggressor, the American Empire in "Little Bird" also believes that it is a victim.

It does not matter how awful things are — there is someone doing these horrible things who actually believes they are doing the right thing. How do you change that person? How do you work towards changing such a person's outlook on the world? That is very difficult, especially when it comes to religion. Those values, even if they are bad and dangerous, are so deeply embedded that most people are not even conscious of them. In "Little Bird" there are many discussions of the power of choices. But what are these choices that can really be made?

For Bishop's speech I just put myself in that character's head. This is easy to do when you accept the fact that these are truths for the character. That is really how they see the world. The character Bishop really does believe that he is doing the right thing. That he and his people are oppressed. There have been casualties on both sides. It's very easy to convince people, even if they are the conquerors, that they are somehow oppressed if their cousin got murdered by someone in the resistance. 30 years into a war Bishop is able to speak from that place. There are people in that crowd who have been touched by the resistance.

How did you create the world of "Little Bird"? Is there a detailed story bible?

There is a logic to the world. Yes, I have a giant book. I asked myself, what does the world look like 2,000 years from now, where there are people called "mods" who are genetically modified both as a form of self-expression but also as a way of being more efficient at their job? The labor market is so competitive that you literally have to start changing your body to get a leg up on the next person. And this all starts to spiral out of control.

Bishop is speaking from a place where he can say that science has run away from us. He can say "Look what we've become in the name of progress!" And what makes Bishop so interesting to me is that there is some truth in what he is saying. Quite often in history with the benefit of hindsight we can see how dictators will take a small truth and manipulate and twist and turn it into something monstrous.

Your family is full of truth-tellers and resistance fighters. How does that inform your work?

It is just part of who I am. I do not think of myself as a political person. But then when I examine my own history I think about so many of the things that my grandparents did working with Green Peace, Amnesty International and for indigenous First Nations rights. My mother stood in front of bulldozers to protect an old growth forest that was going to be cut down in British Columbia. At the time I didn't think much of about what she did and why. But then later in life I thought back about what she had done and my respect for her just grew immensely.

What motivates your art?

It's nothing I've ever stopped to think about. I am a very sensitive person. I was also a very sensitive child. One of my earliest obsessions was Jane Goodall. When I was really young I wrote her a letter saying, "I'm going to study chimpanzees". Even at that young age I just saw us, our humanity in them, and it was just a surreal awakening. I got caught up in this idea of "I need to help them". They don't have a voice. And I actually wrote Jane Goodall a letter when I was about 10 or so years old. She wrote me back on rice paper from a hut in Africa. That letter is hanging on my wall right now in a frame. It is a source of inspiration.

I was also inspired by stories on my father's side of the family because my grandmother and grandfather fought in the Dutch resistance where they smuggled American soldiers to safety, risking their lives to do so. We're not often put in the situation to do things that brave, but I'm just inspired by people who step up and rise to the occasion.

Shares