Banned by MLB, 'Shoeless Joe' Jackson has Hall of Fame-like shrine where he died

GREENVILLE, S.C. -- Nearly 68 years ago, one of the greatest players in Major League Baseball history died of a heart attack in the bedroom of his modest, one-story brick house.

"Greenville is a weeping city today," sports columnist Carter "Scoop" Latimer wrote Dec. 7, 1951, two days after the death of hometown standout “Shoeless Joe” Jackson. "The hearts of thousands in this Southern industrial metropolis throb in sorrow … And the sports world generally mourns the passing of the renowned and respected former major league baseball star."

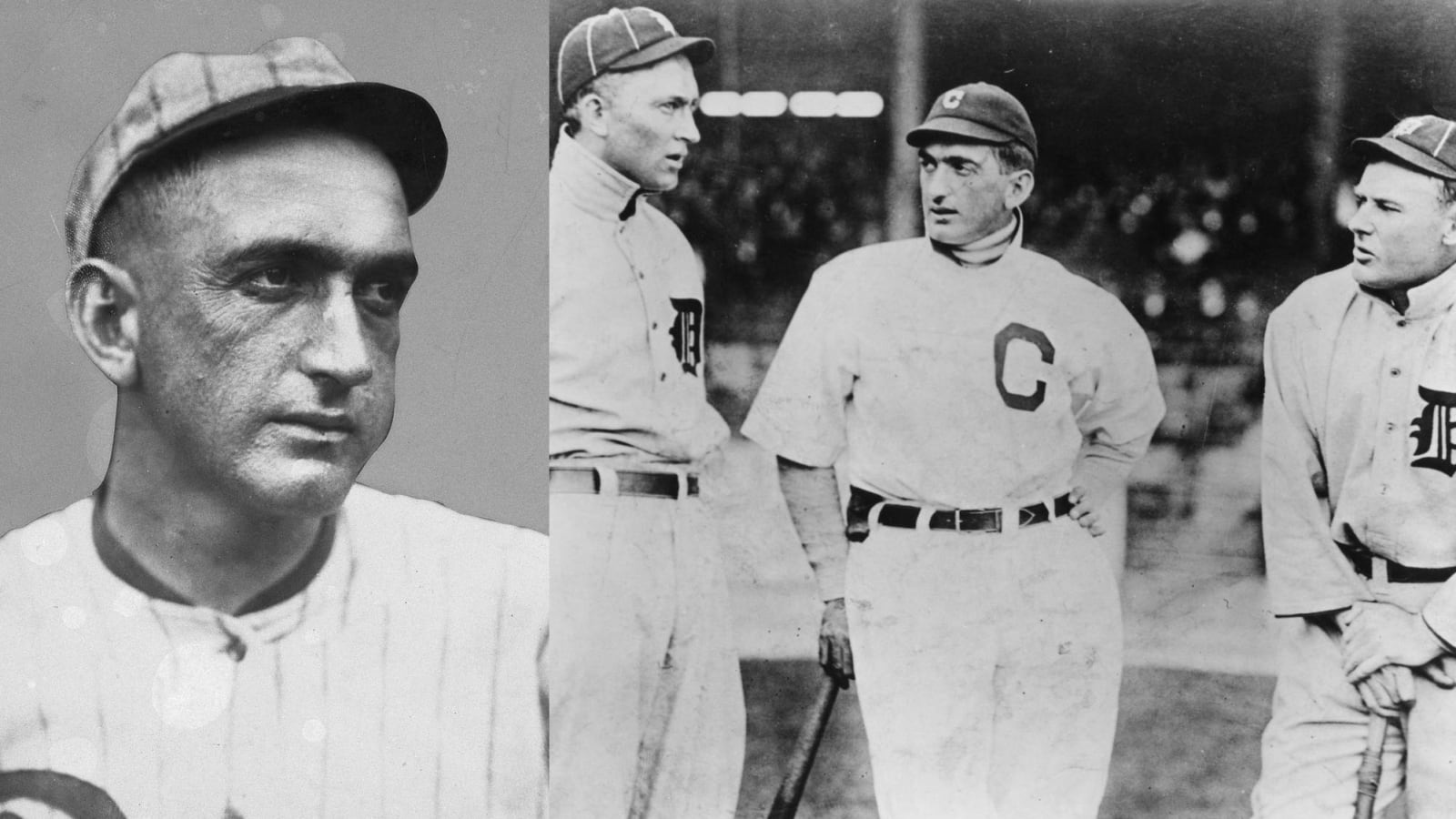

A soft-spoken man with piercing blue eyes, Jackson played his last major league game in 1920. After a 13-year career with the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Naps and Chicago White Sox, he retired with a .356 batting average, third best of all time.

Despite his on-field achievements, Jackson isn’t immortalized in the Baseball Hall of Fame, which will induct the Class of 2019 on Sunday. Instead, the star outfielder -- banished from the game for his supposed involvement in the infamous 1919 "Black Sox" World Series gambling scandal -- is memorialized where he died. The place once described as a “pretty little bungalow” houses the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum.

Jackson loved the home, which, according to Latimer, had “all the modern conveniences of comfort." “Shoeless Joe” and his wife Katie lived in the circa-1940 house for the last 10 years of his life.

In 2006, the five-room house was bought by local entrepreneur Richard C. Davis and moved from its original Greenville location to Field Street, opposite Fluor Field, home field of the Boston Red Sox’s Class A affiliate. The structure was divided into two sections and placed on two 18-wheeler trucks – a move documented on “Flip This House” on A&E.

Davis deeded the house to a non-profit foundation organized by Arlene Marcley, an ardent "Shoeless Joe” Jackson fan, who opened the museum with her husband Bill in 2008. The museum – a shrine to Jackson, really – will soon be moved again, about 150 or so yards away on Field Street. The address will remain 356 Field, homage to Jackson and a reminder of his career batting average.

Until the move is completed sometime next year, the museum will be open only select days and for private tours by appointment. No admittance fee is charged. “I don’t think he would want people to pay to come into his house,” Arlene says of Jackson. “This is still Joe’s house as far as I’m concerned.”

A reserved woman, Marcley, 78, grew up the daughter of an avid baseball player and fan. Her father played minor league baseball. During his career as a U.S. Air Force officer, he managed military base baseball teams throughout Europe. But Jackson didn't draw Marcley's interest until 1996, when she was executive secretary to Greenville’s mayor. In 2001, she helped raise $60,000 for a statue of “Shoeless Joe,” which stands at the main entrance of Fluor Field.

When Marcley speaks about Jackson, her face lights up. Unsurprisingly, she and her husband have strong feelings about his banishment from the game. “There’s so much misconception about him,” says Arlene, 78, who resigned as curator and president of the museum in late May. “Joe Jackson was such a good person.”

“We’ve heard a thousand stories about Joe, and just about every story was about how he was a very kind, southern, country gentleman,” says Bill Marcley. “He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time, and got involved without really being involved.”

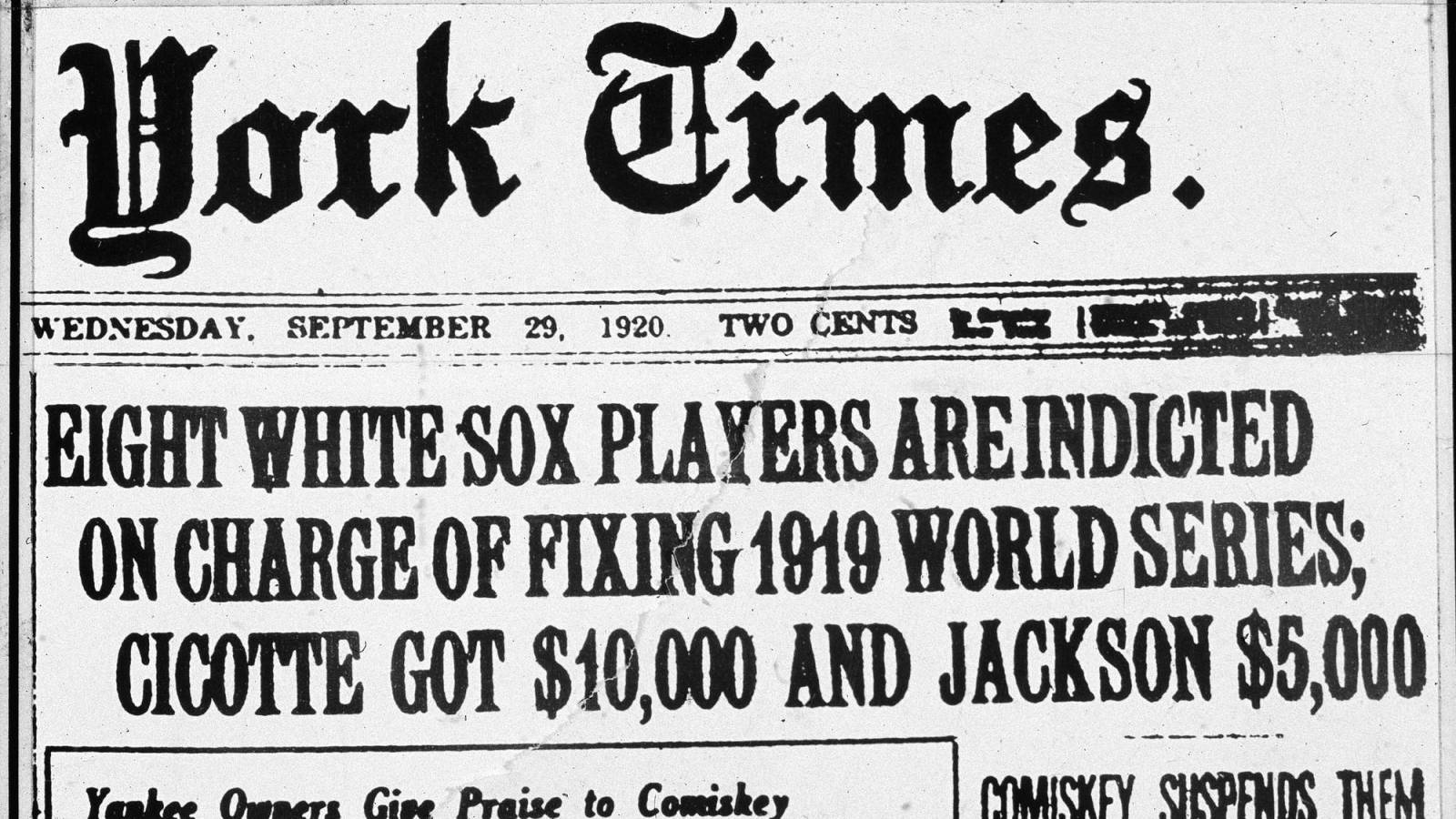

Jackson and seven White Sox teammates were accused of accepting money from gamblers and intentionally throwing the 1919 World Series against Cincinnati. (Chicago lost the eight-game Series, 5-3.) Jackson had 12 hits, a Series-leading .375 batting average and didn’t commit an error against the Reds. Although all eight were later acquitted in a trial, they were banned from baseball after the 1920 season by MLB commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Years later, Jackson’s seven banned teammates said he never attended any of their meetings with gamblers.

The Marcleys insist the museum has documentation Jackson was not involved with the scandal. When Rob Manfred was named MLB commissioner in 2014, the couple was hopeful he would be open to overturning Jackson’s banishment. But in a reply to Arlene’s petition for Jackson’s reinstatement in July 2015, the commissioner saw no basis for re-examining the case, writing: “ … it is not possible now, over 95 years since those events took place and were considered by Commissioner Landis to be certain enough of the truth, to overrule Commissioner Landis’ determinations.”

If Jackson had not been banished, Bill Marcley believes he would have the highest lifetime batting average in MLB history. Ty Cobb (.367) and Rogers Hornsby (.359) rank 1-2. Jackson, who hit .408 in 1911, batted .382 in his final season in the majors, when he was 32.

Near the front door of the museum, a plaque – similar to the Hall of Fame plaques in Cooperstown – includes superlatives from Joseph Jefferson Jackson’s baseball career. Inside, visitors find baseball treasure.

Hundreds of photos from the playing career of “Shoeless Joe” adorn walls. In a framed image from 1920, New York Yankees star Babe Ruth sits on a bench with Jackson, then with the Chicago White Sox.

“I copied Jackson's style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen,” reads a quote below the photograph from the Bambino. “The greatest natural hitter I ever saw. He's the guy who made me a hitter."

In the living room, a massive enlargement of a somber-looking Joe and Katie Jackson, taken the day they wed in 1908, dominates. On a wall, above a window to the left of the wedding-day photograph, is a huge copy of Jackson's signature. Because her husband was illiterate, Katie showed him how to write his name on a small piece of paper. “Shoeless Joe” kept the signature in his wallet so he could copy his name for important documents.

On a red Easy Chair in the parlor is a reproduction of “Black Betsy,” the bat Jackson used in the major leagues. The original “Black Betsy” was sold at auction in 2016 for $583,500. The enclosed porch of the house is now a library, stuffed with hundreds of baseball books.

Perhaps the most visited part of the museum is the bedroom where “Shoeless Joe” died at 64. Visitors find bricks and a seat from old Comiskey Park, Jackson’s home field from 1915-20. On the wall hangs a panoramic image that includes Jackson and the best players from his era.

Mike Wallach, managing director of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum and Library, has big plans to promote the museum when it officially reopens. His son Daniel, an ardent collector of “Shoeless Joe” memorabilia, will become museum executive director. Some of his Jackson collection will be displayed in the museum -- including dirt from many of the ball fields “Shoeless Joe” played on in the Greenville area.

HOW 'SHOELESS JOE' GOT HIS NICKNAME

Growing up in the eastern corner of Pickens County, about 7 miles from Greenville, Jackson came from humble beginnings. Instead of going to school, he began working in a mill when he was 6. He never learned to read or write.

In 1907, Jackson signed a contract to play baseball for the Greenville Spinners, a South Atlantic League team. The following year, at age 20, he earned his famous nickname.

During the early part of the 1908 season, Jackson’s new cleats were giving him blisters on his feet. Before a late-inning at-bat, Jackson reportedly slipped them off and then hit a walk-off homer. "You shoeless, son of a bitch!” a fan yelled from the stands.

Others tell a slightly different version of how Jackson acquired his famous nickname. As that story goes, he played the entire second game of a doubleheader without cleats. In the seventh inning, he hit a triple, and as he arrived at third, an opposing player yelled “Shoeless” and an obscenity. Carter “Scoop” Latimer, a young sports writer at the time, wrote about the incident for The Greenville News. The story hit the wires the following day, and a nickname was born.

--Dave Holcomb

More must-reads:

- My crazy life as 21-year-old road manager for The Famous Chicken

- 'Unsung heroes': In Indiana, a quirky hall of fame honors sports mascots

- The 'Active MLB strikeout leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!