Bone-Crushing Hyenas Lived in Canada's Arctic During the Last Ice Age

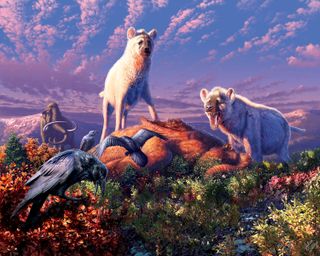

During the last ice age, bone-crushing hyenas stalked the snowy Canadian Arctic, likely satisfying their meat cravings by hunting herds of caribou and horses, while also scavenging mammoth carcasses on the tundra, a new study finds.

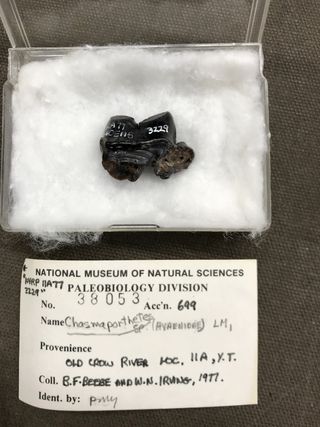

The big finding — that ancient hyenas lived in the North American Arctic — is based on two tiny teeth, which archaeologists found in Canada's northern Yukon Territory.

The two teeth fill a gaping hole in the fossil record. Researchers already had evidence that the wolf-size hyena known as Chasmaporthetes lived in Mongolia and — after crossing the Bering Strait land bridge — Kansas and central Mexico. The newfound teeth show where the Chasmaporthetes lived between these two places: about 4,000 miles (6,500 kilometers) away from the Old World in Mongolia and 2,500 miles (4,000 km) northward of Kansas, the researchers said. [Image Gallery: Hyenas at the Kill]

In other words, Chasmaporthetes was able to adapt to all kinds of environments, study lead researcher Jack Tseng, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University at Buffalo in New York, told Live Science.

Archaeologists originally found the two fossil teeth in the 1970s, in a fossil hotspot known as Old Crow Basin. But nobody ever published studies on the teeth, which languished for decades in the collections of the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottowa, Ontario.

Tseng learned about the teeth only through word of mouth. Intrigued, he hopped in his car and drove the 6 hours from Buffalo to Ottawa in February, the dead of winter. The teeth, a molar and premolar, were so distinct, that "within the first 5 minutes, I was pretty sure this was Chasmaporthetes," he told Live Science.

When most people think of hyenas, they picture the carnivores roaming Africa today. But hyenas actually arose in Europe or Asia about 20 million years ago. Only later did hyenas make their way into Africa, and an even smaller number trekked across the Bering Strait land bridge to North America, at least according to the preexisting fossil record.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The teeth are challenging to date because they were found in the inner bend of a river — meaning that the current washed them away from their original resting place. But based on the geology of the basin, the teeth are likely between 1.4 million and 850,000 years old, Tseng said.

These teeth aren't from the oldest hyenas in North America, however. That prize goes to the 4.7-million-year-old hyena fossils found in Kansas, Tseng said.

He added that these ancient hyenas never ran into a human. The beasts went extinct in North America between 1 million and 500,000 years ago, long before humans arrived in the Americas. (One of the oldest human traces in the Americas is a 15,600-year-old footprint in Chile.) It's unclear why these hyenas disappeared, but it's possible that other voracious ice age carnivores, such as the bone-cracking dog (Borophagus), giant short-faced bear (Arctodus) or hunting-dog-like canid (Xenocyon) took over their habitats and outcompeted them for prey, Tseng said.

Today, there are only four living species of hyena — three bone-crushing species and the ant-eating aardwolf. Given that Chasmaporthetes was a bone crusher too, it likely played a large role in disposing of carcasses in ancient North America, much like vultures do today, Tseng said.

The new study takes a much-needed dive into carnivore evolution and diversity in North America, said Blaine Schubert, executive director of the Center of Excellence in Paleontology and professor of geosciences at East Tennessee State University, who was not involved with the study.

"It has long been hypothesized that hyenas crossed the Beringian land bridge to enter North America, but evidence was lacking," Schubert told Live Science in an email. "These new fossils support the Beringian dispersal hypothesis and dramatically increase the range of Chasmaporthetes."

The study was published online today (June 18) in the journal Open Quaternary.

- My, What Sharp Teeth! 12 Living and Extinct Saber-Toothed Animals

- 10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America

- Ice Age Animal Bones Uncovered During LA Subway Excavation

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular