Today we share photographs with each other in a fraction of a second through countless global platforms, including Facebook messenger, Instagram, WeChat and email. Moments after snapping photos on our personal digital devices, we show them to people all over the world, from close family members in private messages to complete strangers via public profiles. In fact, our daily lives are so saturated with image-sharing that it’s difficult to remember a time when instantaneity was perceived as more magical than mundane.

But the evolution of photography in the digital realm transformed more than our daily, inconsequential imaging habits; it also radically changed the state of photojournalism. In an era when photographers sent rolls of film (housed inside secure packages) directly to publications, creating contact sheets and images for stories with rapid turnover, each minute in the air was time lost.

This prompted the invention of the wirephoto, a technology that today feels just as magical and surreal as watching a daguerreotype develop for the first time. Invented in the 1920s—predating our current texting methods by many, many decades—a wirephoto was the transmission of a picture by telegraph, telephone or radio. At the time of its invention, it required a dedicated phone line, and the necessary machines were incredibly large and expensive. But in a sociopolitical climate that increasingly used photography as evidence for news and information, the magic of an inked needle dashing about a page to manifest an image was a surreal accomplishment. This magic was internalized as an indication of an image’s truth and power, contributing to the mythology of photography as proof of what actually happened—an undeniable record of “real” events.

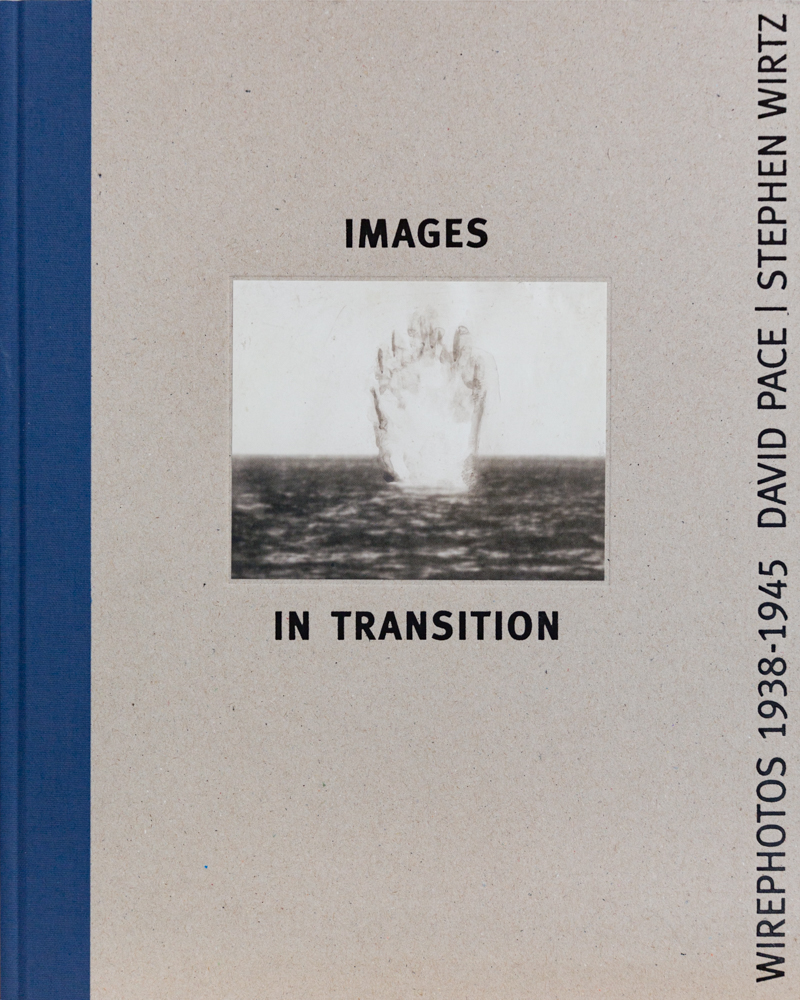

Inspired by the legacy of this lost photographic process, artist David Pace and collector Stephen Wirtz constructed Images in Transition: Wirephoto 1938-1945, a new photobook comprised of a selection of wirephotos transmitted during World War II. Flipping through the individual works, readers encounter peculiar, off-beat gestures, intense symbolism and allusions to destruction. Each fragment is as beautiful as it is violent, contributing to the age-old debate surrounding the ethics of photojournalism, and the pursuit of visual records in the wake of human suffering.

But the work isn’t just about the ethical questions that arise from that instantaneous moment when a photographer feels the click of their shutter. At the end of the duo’s sequence of manipulations, a set of original wirephotos are included for readers to inspect each recto and verso, equipped with press stamps, crop marks and acquisition numbers. An accompanying essay on the technology’s history is also included, revealing the multiple levels of retouching that were necessary throughout the wirephoto process.

“In preparation for transmission,” author Mark Murmann explains, “a photographic original image had to be carefully retouched to clearly define and accentuate to the contours of the image.” He later continues, “The received wirephoto images typically required additional retouching to clarify or emphasize shapes and figures present in the original but obscured by the artifacts—the dots, lines and irregularities—of the transmission process. Occasionally retouchers even introduced new content.”

These multiple layers of retouching are extended in the alterations made by Pace and Wirtz who, after scanning each image, re-crop and enlarge certain bits to expose both the glitches and human intervention in the photos, raising further questions about our reliance on photographs as hard evidence devoid of interference. On close inspection, an explosion on the front cover seems to have been intensified with watercolor, and the shadowy contrast we see in the looming silhouettes of buildings and soldiers are more akin to illustrations than photographs.

By bringing all these crops and interventions together into one study, Images in Transition acts as a record of the duo’s compelling aesthetic journey, as well as a model for questioning the problematic history of photojournalism. It is an artwork as much as it is a slice of cultural criticism, untangling how a deeper knowledge of the history of the medium we cherish is necessary for understanding its mechanisms today, from iPhone photos of candid moments to stylized prints in a fine art gallery. As Murrmann states in his introduction to the work, “The source material used here came from World War II, but don’t mistake this for a book of war photography. It’s not even really a book of photography. You are holding a book rooted in photography, made of pieces of photographic images, but calling it a photobook would be a stretch. Images in Transition is a body of work rooted in history, photojournalism, and technology. Ultimately, it is a book of art.”