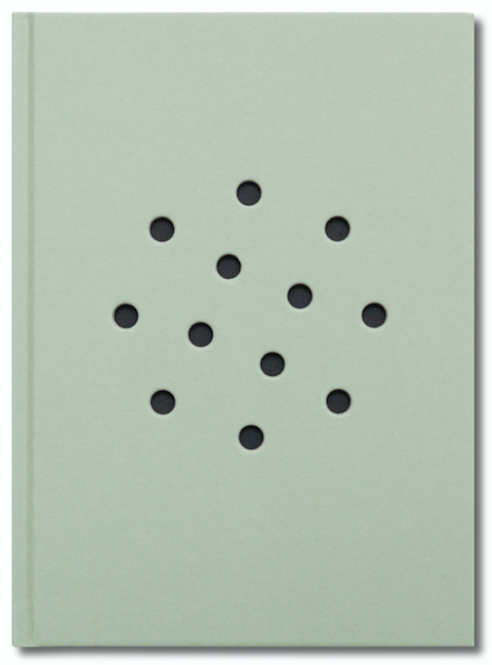

When readers first encounter For Birds’ Sake, a photobook by Maria Sturm and Cemre Yeşil, they are confronted with a peculiar contraption. A patterned fabric jacket envelops the book, whose pages can only be reached after unzipping the tight sheath. Once the jacket is removed, a simple seafoam-colored cover reveals itself, perforated with small holes and absent of an obvious title—layers of strange details that allude to something we have yet to recognize.

But once we open the front cover, leafing through the pages within, Sturm and Yeşil’s photographs reveal the book’s outer shell is so much more than arbitrary excess and flouncy artistry. The images recount the story of the kuşçu (‘birdman’ or ‘fancier’ in Turkish) of Istanbul—keepers of live finches who consider themselves the composers of their birds’ beautiful songs. The enclosures that they use for their feathered companions resemble the cover of Sturm and Yeşil’s book—boxes with a cluster of holes for ventilation and breathing, all encased in a tightly-zipped outer case.

Sturm and Yeşil met at a workshop in 2012, and both of their practices are rooted in an emotive, paced aesthetic that harnesses the beauty of ambient light. In particular, Sturm’s fascination with photography began at an early age as she sifted through family albums, selecting prints to decorate her bedroom. She also cut out and collected pictures from magazines and other source material, which moulded her fascination with softer imagery.In contrast, Yeşil’s father was an amateur photographer himself, and crafted a darkroom in their home before she was born, later teaching her how to use a camera when she was a teenager.

After pursuing photography in such different contexts, the collaboration between Sturm and Yeşil was a useful learning experience for both of their engrained practices. “I learned a lot from Maria’s way of thinking and working with images,” Yeşil explains. “Throughout our collaboration, she was the more structured one, and I was the one who operated with my gut feelings. We often joked with each other about this—me telling her that she was too German in her approach. But in the end, our differences resulted in a dynamic cocktail of photographs.”

The idea to come together and create a visual story about the kuşçu dawned on the duo during a conversation about animal noises. “We were talking about how the sounds of different animals are pronounced in different languages, such as Turkish, German, Romanian and English,” Sturm recalls. “We were fascinated by the way languages record these sounds so differently, even though in reality, it is the same sound. We spoke about how the language you speak changes the way you hear and perceive things.”

“Then Cemre remembered a video she saw on YouTube that went viral in Turkey, showing a birdman verbalizing bird sounds. We started imagining pictures of this relationship, and decided to pursue the story photographically. Without knowing any of these men, and after a number of dead ends in our field research, we went to a neighborhood where someone mentioned we might find some of the kuşçu. We walked down a street and noticed a mysterious white box, and then another, and then another. Then, as we looked around us, we found ourselves surrounded by men with birds.”

And so the project began. The two photographers started making pictures simultaneously in the same spaces with the same type of camera. “We see ourselves as one person in this project,” Sturm explains. “When we started editing the images, we threw all of them together, and it never mattered who took which picture. Sometimes we would be looking at an image we really liked, and one of us would compliment the other on the beautiful composition. The other would then say: ‘Actually, you took that photograph.’ Something really extraordinary and beautiful happened with us, where we didn’t actually know or care who took a great image. It was our work, and we were one.”

This symbiotic approach resulted in a collection of soft, poetic images that gently guide viewers through the daily lives of the kuşçu and their tiny companions. Gentle pastels and nighttime lighting set the contextual ambiance of each scene, which depict everything from the interior gathering places of the birdmen to their outdoor lives. We see the coffee and tea houses where the kuşçu meet up to socialize and compete, recognizable by the hooks on their walls and ceilings for hanging their cages. We also see the men’s relationship to their natural exterior surroundings, planting new saplings with an understanding of the importance of balance in nature.

But who exactly are these men, and how did this tradition come about? In Istanbul, the keeping and breeding of songbirds dates back centuries. “Since the time of the Ottoman Empire, Istanbul has been a very important city for aviculture,” Yeşil explains. “The city’s geographical location for bird migration has led to the establishment of a huge culture devoted to birds and their care.” In particular, Bosphorus—a significant waterway in northwestern Turkey—boasts a wealth of natural habitats, including wetlands, forests and numerous bodies of water, which all foster an organic relationship between men and birds. Today, capturing finches in the wild is illegal, and the kuşçu risk heavy fines by perpetuating the tradition close to their hearts. But still these men persist, choosing to ignore the new regulations, continuing the practice of catching wild finches to keep as their own, training and caring for them to compete with one another.

To an outsider, this practice seems strange. Observing the lives of these men raises questions about masculinity and femininity in the tradition, where women are essentially absent from the narrative (aside from Sturm and Yeşil themselves, who are there documenting the process). Women are left in the dark when it comes to this daily ritual, and the birds these men care for so deeply are also continuously shrouded in pitch black—an old trick that compels the finches to reach their sweetest notes. Their obsession with the birds is palpable, seen everywhere from permanent references tattooed on the men’s bodies, to the selection of decor that adorns their various meeting places. By photographing these fringe moments, the weight and importance of the birds is made even more clear, as their presence saturates images that might, at first glance, appear to be outtakes.

But perhaps the most intriguing feature of the book is what we never actually see: the birds themselves. Their absence is an interesting choice, especially since they are the implied protagonist throughout the work. What’s more: we can’t hear them through photographs, though their beautiful music is the main thread coursing through the daily lives of the kuşçu. Instead, Sturm and Yeşil sculpt a narrative about the tiny creatures without a direct visual or auditory reference, relying on atmosphere and artistic approach to weave together the intricate components of this multifaceted story.

When asked about this absence, which takes a few readings of the book to register, Sturm explains, “This is an embodied feature of the medium of photography. Although photography is about revealing and showing things, it keeps a lot to itself, because we never know what the photographer decided to exclude from the frame. The kuşçu believe that their birds sing more beautifully in darkness, so the cages are always covered—sometimes with two or three layers of cloth and paper. You never actually see the birds, even though everything they do is about them—what they talk about, the decorations on their walls, their cellphone wallpapers. These men are only interested in listening to their birds, not looking at them, even though they are historically known for their beautiful appearance.”

So while the story of the kuşçu and their finches forms the backbone of this book, Sturm and Yeşil reveal that in the end, their publication is truly about the time-old paradox between love and ownership. “The birdcage is a metaphor for anything that one can love with a burning passion,” Sturm reflects. These beautiful photographs, outlining a quirky, seemingly unfamiliar story, are far more than a standalone documentary record. “Although we are telling a story rooted in tradition, the work also questions what we do to the things we care for, questioning the contradictions between love, possession and pleasure.”