In its framing of communities simultaneously mundane and mystical, Morgan Ashcom’s work questions assumptions about the very nature of photographic narrative. His first book, Leviathan, chronicled Ashcom’s immersive experience in the microcosm of Skatopia, a small anarchist Ohio skateboarding community. In his 2017 book, What the Living Carry, impressions of the fictional composite hamlet of Hoys Fork unfold like divinations—a mapping of people, environs, and nature that feels immanent and intimate, revealed and unraveled, full of investigations about the ways inheritance and identity are knowable, and yet not. The hushes and pauses of these resonant moments contain a reverence for history, an endless and haunted past both factual and embellished. This space is contextualized by learning Ashcom’s birthplace is the tiny town of Free Union, Virginia, at the edge of the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains.

Throughout the book, Ashcom’s narrative is interleaved at various intervals by typed carbon copy letters with cross-outs and errors. They are addressed to “Morgan” and signed “Eugene,” an idiosyncratic, enigmatic and dyspeptic Hoys Fork citizen who heads the Center for Epigenetics and Wellness of the Spirit. “Genetics is all about expression,” Eugene writes to Ashcom in one of the book’s letters. “It is our blood that guides us…in any creature, cells are bound to different fates despite having identical DNA.”

Eugene carps about the transgressions and minor persecutions he suffers from his neighbors, philosophizing about the way heredity affects his own emotional make-up. His anecdotal reminiscing recounts pedestrian occurrences and a dream leading to the creation of a map, also tucked into the book. The map includes local landmarks: Eugene’s own Center, Rivanna University (whose students he disparages), the Old Department of Corrections, a Boneyard, Church, Hometown Inn, Lawsons Castle and the New Department of Corrections.

Although Eugene’s stationery locates Hoys Fork (an eponymous Kentucky river and school) in Rivanna Co. (a river in Virginia), absent are the additions of state, area code, or year on his letters. We are left wondering where and when the denizens of Ashcom’s photos—and Eugene—reside in Ashcom’s imagination. Yet we are also implicitly invited to infuse this tale with our own secret feelings and fears about a place, to allow our own hopes and fantasies to disrupt narrative. We are left with the illusory nature of the tangled undergrowth of intertwined facts and fiction. We are left with only questions.

In conversation, Ashcom’s creative terrain ranges from Dante to Dostoevsky, Faulkner and obscure Hungarian films, Beckett and a quote from The Bible As It Was that he characterizes as an “interrogation of the past and a pre-lapsarian world.” It’s unsurprising that he has taught courses on photography, literature, and the photographic book. The work of contemporary photographers he admires, such as Susan Lipper, Justine Kurland, and Sally Mann, is easier for Ashcom to talk about than his own.

Doreen Schmid: Dualities are both implicit and explicit in your work. You seem to flush out tension between the imagined and physical worlds by interacting with objects as dream triggers. Do you understand the book in that way: as a physical object containing an active mystery?

Morgan Ashcom: I couldn’t agree more. I think it’s important to have that experience with art. I certainly have things—books and objects—that I return to, and it’s a connection to the idea of place and land that is evocative for me. So when I walk around in these places and see the way vines wind around a tree and the way a hill rolls, these things enliven a landscape and cause me to, as you say, have a dream trigger—have my vision activated and energized in those spaces. That’s where it becomes narrative for me, and I like to think the pictures function as dream triggers for people looking at them.

DS: That speaks to honoring the inherent energy in something, and how the dream trigger object is a talisman. You capture that spirit of mystery and circle it, but you don’t colonize it. There’s almost a resistance to conclusion—a kind of Beckett-esque treasure hunt in the way you are playing with truth. It’s the sad irony of Beckett’s Happy Days—at once a maze and playground.

MA: Yes, Beckett. I call it “comic existentialism.”

DS: And that relates to Eugene writing, “Inside was like a maze and there was no way to leave and there was a bunch of beautiful people with all the potential in the world doing various things in disarray and such. But no one had a direction—”

MA: There are a lot of threads that come together for me in what you’ve been saying. First, to address Eugene: I think it was Margaret Atwood who once said, “Wanting to meet an author because you like his work is like wanting to meet a duck because you like pâté,” which I think alludes to issues that arise when we closely conflate works with their authors.

Faulkner said something similar: that he worked from his observation, imagination and experience, but he would never bother to translate any living person or thing into fiction—that it takes a human being an entire lifetime to become whole. But the artist hasn’t got that much time. So there is a fair amount of fictive compression at work.

DS: That recalls one of Eugene’s letters: “It is how this raw data is interpreted that matters, and events in our lives can permanently alter its interpretation.”

MA: Yes. So the translation of Eugene from the various inspirations is so indirect that it’s almost not right to talk about it. It’s also true that I took hours and hours and hours of field recordings.

DS: Of what?

MA: When I go out photographing, I put a recorder in my breast pocket. I record snippets of conversation, and I also partly do it for safety. The police will oftentimes stop me, and it’s important to have a document of what was said to protect yourself.

DS: When you’re in the woods with bird life—that dense brush and those tangled vines—do you record those sounds too?

MA: Yes, definitely.

DS: When do you listen to a recording after you’ve made it?

MA: I listen to it before I write, in the car when I’m on an eight-hour drive. Something to get me into that space again.

DS: Does this immersive concept connect to how you use 3D elements to expand on the photos from the book? Both your 2018 Houston Center for Photography and Candela Gallery (in Richmond, Virginia) exhibitions contained 3D elements.

MA: It’s an extension of what I started to do in Leviathan, and also had to do with this tension between an imagined world and the physical world that was in front of the lens. In that project, I collaborated with people to make narrative photographs related to a myth. The 2018 exhibitions of What the Living Carry extended that process, beyond the 2D plane of the photograph.

© Morgan Aschom, courtesy of the artist.

DS: Those exhibitions included not only prints but—as an extension of the main project—vines, Eugene’s desk, and video. What do these elements add to the constructed reality of the environment you’re creating? Do they reflect the project’s vision in a different way than the book?

MA: Yes, the exhibition was a different experience than the book. When someone walked in, they saw Eugene’s desk sitting there, and they could drop off a piece of their DNA to be analyzed. There were a pair of scissors on his desk, and you could cut a piece of your hair for him to use. Another aspect of the exhibition were the rubbings. Everyone who came in made a rubbing of the marker, and signed it “Studio” with their name, year and where the rubbing was made. As the marker moves around to different venues, there will be a collection of rubbings that show where it’s been—mirroring the fractured nature of Hoys Fork. To make a rubbing is a way of becoming a citizen.

© Morgan Aschom, courtesy of the artist.

DS: In the book we learn that Eugene intends to test your DNA as part of his studies in human and animal DNA. Does the idea of DNA rooting us in landscape (as well as ourselves) amount to a palimpsest, making it impossible to return to the idea of the original grave, suggest that we are all composites of our lifetimes? On your website you explain that growing up you frequented a forest with markers placed there by former slaves. Jo Hoy’s was the only one of these with any legible writing but you couldn’t make rubbings of it to learn more about the family because the stone was too rough. State archives yielded no information. You write that “Hoys Fork originated from the absence of information about the Hoy family and the lack of places named after all-but-forgotten slaves.” In the exhibitions you offer the participatory element of creating a gravestone rubbing. Is this a way of addressing how Jo Hoy’s gravestone is excised from history?

MA: Yes, Jo Hoy and many like him. History reveals itself on its own terms. I’m inviting people to engage with it in a physical way that is different from how most people think of history. We tend to think of history as something we experience in text, and as something removed from our immediate experience. But Hoy’s marker is a visual and physical experience. It’s immediate, and the rubbings are made from an impulse to preserve that moment, to say, “I was here.” The text on Hoy’s marker doesn’t translate directly with rubbings, so something new is created. Most of them are abstract—more of a residue that is produced, like the carbon paper’s relationship to the letters. It would take a very dedicated person to read one of those carbon letters.

DS: What do they look like?

MA: They’re beautiful, in this rich matte black carbon, in a grid on the wall.

DS: In the book, the recto and verso of each letter are individual, reinforcing duality, the legible and illegible, the immutable vs. permeable. The reversed text on the back of the carbon copies recalls photo negatives that we cannot “read,” in the sense of understanding. The reversed text is as indecipherable as Braille to the seeing. And in the show?

MA: The front and back are two separate objects, usually hung on opposing sides of the gallery or a dividing wall running through the space.

DS: How do you see the persistence of the photobook—its visceral value as a permanent object—in relation to the transience of exhibitions?

MA: The book is something that can transmit the work over a longer arc of time. The gallery show is ephemeral—a one-off experience, a different sort of immersion. The book is the lasting articulation, the place in which the work resides and can be retained over time. I like the idea that the photographic book has adopted the same form as illustrated manuscripts and novels.

These are the core forms across all societies that retain the narratives that tell us who we are, for better or for worse. And it’s an acknowledgement of the power of those narratives within that form.

DS: Is David Lynch an influence for you? Hoys Fork is completely colloquial, but is like Twin Peaks in its strangeness. Does it operate as a real place you have transformed into a fictional construct?

MA: Part of what interests me about Lynch is how he positions the grotesque within mundane settings. All of it exists at once, which feels true to life from what I’ve observed. I like putting opposing forces in uncomfortable proximity. It’s a tension I also found in an essay T.S. Eliot wrote about Dante. In it, he writes about “the possibility of fusion between the sordidly realistic and the fantasmagoric, the possibility of the juxtaposition of the matter of fact with the fantastic.” Dante has been an interest of mine for a long time. I like the idea that The Divine Comedy begins in the “dark wood” with Dante walking around lost, and Virgil coming to get him so that they can go on this trip.

DS: The conceit of a journey?

MA: Yeah, but the idea that it starts with solitary reflection, in the woods. That resonated with me because What the Living Carry began by making pictures alone in the forest. The town came about later.

DS: What are you doing technically that renders the images so atmospherically charged, like they’re conjuring something?

MA: That’s part of why I was interested in using the large format camera—because of how richly it describes the world. It pushes the descriptive power of photography. The greater extent to which something is represented, the more we feel the absence of the actual thing. So despite the level of detail, there is still so much for the viewer to fill in, or “conjure,” as you put it. So the atmospheric charge may not be inherent to the work so much as it is to the viewer.

DS: Is this time frame part of that endless past that is often associated with the South? Hale County, Alabama is marked by Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, as well as William Christenberry’s photos. But Hoys Fork seems to be a mythical composite landscape, more comic and poetic, and more akin to William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, where he claimed: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Do you feel the work connects to that Gothic, self-mythologizing South—the idea of redemption and reclamation? How does that still resonate today, especially considering current events?

MA: Not so much Gothic or Southern—Hoys Fork is not a distinctly Southern town, it’s just rural. I think of it in terms of Romanticism, of seeing ourselves reflected in our environment. But if you look at a contemporary environment like Hoys Fork, there’s a level of irony that replaces the earnest Romantic cliché—I’m thinking about the picture of the Family Dollar with a crater in the parking lot and rainbow in the background.

Another picture from Hoys Fork, the one of the painted mural, speaks to that theme of self-mythologizing. It’s a depiction of a town’s depiction of itself on one side, and the main street on the other. In the background there’s a street corner where an incident takes place in a separate picture. Aside from the Native American’s skeptical expression towards the church, everything seems fine. That’s the nice origin story we tell ourselves because we’re still invested in the negation of our past, of who we are. I sit here talking to you from Charlottesville, Virginia, where recently this—this negation—was on full display.

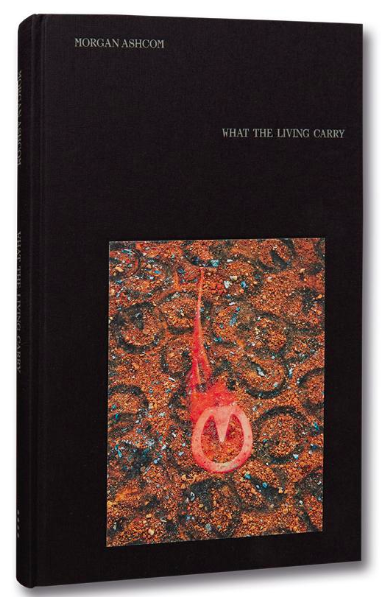

DS: What about the red horseshoe image? Does it relate, being featured on the cover, to one of those burning questions? The red color is so bright it seems the metal is still hot.

MA: It’s the hot shoe and red clay in late August light—the soil that we have in a lot of places—Ohio, Virginia, South America. I liked the idea of a horseshoe making a stamp on these places. A lot of the book is about residue, about things that are evidence of past action. That horseshoe and many others have been dropped on that same red soil, in different places.