In 2011, Tanyth Berkeley began photographing a woman named Ruth Cooke, an ostracized member of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (a denomination of Mormonism that continues to practice polygamy). Ruth, rumored to have 53 siblings, lives alone in the desert of Arizona, excommunicated from the Church after speaking out against its abusive culture and seeking justice for the women and children who have been victimized. Her five children were taken away from her, she was sent to jail, and she was left with no choice but to live alone in poverty. Berkeley photographs Ruth’s isolation in her book The Walking Woman eagerly and unapologetically, and her admiration for Ruth’s resilience is resonate and inspiring.

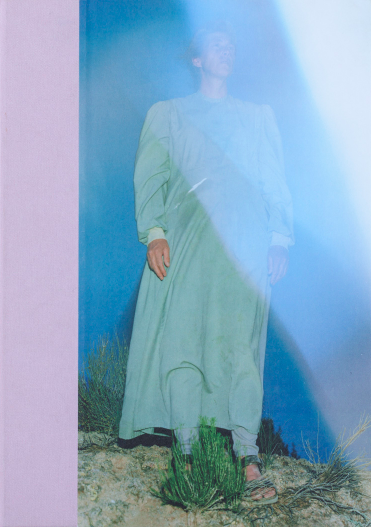

Halfway through The Walking Woman, Ruth’s presence fades into landscape images and cloudy color washes. The reader suddenly meets a new woman named Spice Slaymaker, who lives alone in a trailer in the desert of Utah, and whose story starkly echoes that of Ruth Cooke. Ostracized from her community due to drug use, Spice also lost five children, was also imprisoned, and now also lives in solitude. Berkeley emphasizes the similarities between Spice and Ruth by clothing them both in Ruth’s prairie dresses.

The stories of these two women tell a much more nuanced tale than one of isolated marginalization. Berkeley’s images are made with such honest respect that Ruth and Spice find power throughout the book, not despite—but because of—their victimization. There is much healing and hope to be found in her photographs, but not without a deserved critique of a society that seems to overlook her protagonists. The images in The Walking Woman raise concerns about capitalism, the environment, and misogyny—but not without sacrificing extraordinary beauty.

Dylan Hausthor: A large part of The Walking Woman is concerned with the search for power. The two protagonists seem to float between positions of victimization and pride. The way your images function seem to echo that sentiment, showing both the highs and lows of their experiences, sometimes offering support. How did the camera play into your interactions with Ruth and Spice?

Tanyth Berkeley: The Walking Woman reminds us that despite past trauma, injustice, and pain, there is always the possibility of restoration. In the book, this happens via the landscape. The photographs draw parallels between the abuse and mistreatment of women and the poisoning and pollution of the earth, which are both born from a similar mindset. When abuse of power is at the core, there is a definite need for a paradigm shift. We need to call attention to, and acknowledge, the very real history of violent oppression, colonization and intersectionality, as well as the loss of species and plants by the thousands and counting.

In my work, I tend to value fragile and vulnerable subjects. I feel like this teaches us how to be better and how to do better. In The Walking Woman, the camera allowed Ruth and Spice, who felt invisible, to be seen. This is the kind of dynamic I’m working with. My own experience with loss and grief—living with the wolf at the door—comes into play as well. I’m not just a spectator, but a participant. I’ve lived on the edge of obscurity and know both the joy and terror of it. The camera allows for a celebration of strength in surviving extraordinary events.

DH: The book borrows its title from a short story by Mary Austin, published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1907, and the story is also the only text in your book. The intersection of the text’s narrative and your photographs’ story weave in and out of fiction and nonfiction in such a compelling way. How do you hope these threads combine to tell the full stories of these two women?

TB: The fact that Austin wrote The Walking Woman more than a century ago is incredibly poignant. In the original book dummy, the text was presented as one piece. But during the design process, we decided to break the text up across the book. This decision was made, in part, because when you read the paragraphs on their own, it’s almost uncanny how relevant they are to the narratives of the women in the book—and sadly, the narratives and treatment of women in general.

I think the experience of reading a photobook operates something like this: you look through the book once, probably without reading it and only taking in the photographs. Then you read it again, this time taking in everything, including the text. The experience creates a feedback loop that feels really appropriate with my work—the past informs the present and the present exists with the past. In this way, instead of coming across as anachronistic, the text feels like a continuation of the ever-present possibility.

This is the kind of joy I referred to earlier, and there is always the possibility to not participate in this culture. As far as the fiction and nonfiction, stories deeply embed themselves in me and my images with the lines blurred. I think we are all part fiction, myth—nothing is set in stone, memories are plastic and our roles in life change. The funny thing is, I had no knowledge of Austin’s story until after I made the work. Happy accidents are a big part of my practice, so what started as a portrait of Ruth then unfolded into something far more interesting by not exerting control—by letting go of my expectations of the project, I was able to let more in.

By letting things take their natural course and by surrendering to the drifting and the unknown, I met Spice. The fact that Ruth and Spice have things in common says a lot about the odds. I think there are many women whose stories are unknown and whose voices are unheard—“living in quiet desperation,” to quote Henry David Thoreau. As I got to know them, I realized that the similarities in Ruth and Spice’s lives were almost uncanny, and so I collapsed their stories together to create a portrait of women alone, women adrift—hoping that their individual stories would surface in the details. When I dressed Spice in Ruth’s dresses, the incongruous costuming makes the viewer aware of my voice—my auteurship—and suggests that this is not just a straightforward story; there was, in fact, some omniscient narration.

DH: Color is a hugely important source of content in all of the images in the book. The washed out, faded pastel palette is as much a character as the Ruth and Spice. How did you begin to make images like this? What does it add to their stories?

TB: To be honest, I was initially drawn to the dresses worn by the FLDS women, covering their bodies in pastel from ankle to chin. Having spent a short but profoundly memorable portion of my childhood growing up in Colorado, I have a real love for these colors: the palest pinks that make up a sunset, the faded desert tones of the southwest, golden yellow sunlight and blue skies. It surfaces in a lot of my work. For example, I was working with a similar palette in my previous work, in part to complement the complexion of women with albinism I was photographing, and to also simulate flowers in another project called Orchidaceae, which brought young women I met on the subway into daylight.

In The Walking Woman, the light colors contrast with the darkness of the narrative. Sometimes the candy-coated sweetness can be symbolic of what’s expected: a kind of submissive femininity that’s perversely childlike, innocence imbued with obedience and naiveté. In the book, I felt it was important to contrast the jejune surfaces with the color red—the color of blood and rebellion. It also mirrors the red tones that naturally appear in the landscape near the hot springs, a symbol of a polluted and toxic environment. My decisions on color probably had something to do with the fact that I was pregnant when I was shooting the work, thinking a lot about my child and making preparations by looking for the softest and sweetest things, from vintage handmade quilts to gently-used clothing. The infusion of these choices takes on a bittersweet quality since both Spice and Ruth were separated from their own children.

DH: The design of the physical book The Walking Woman feels so integral to the story. Do you think this work could exist as an exhibition? What do having pages to turn add to the work?

TB: The design definitely plays into the success of the project in the book form—this was the result of many years of simpatico collaboration with Christina Labey, Creative Director and Co-Founder of Conveyor Editions, and the designer Elana Schlenker. If I were to exhibit the work on the wall, it would be a series of visual excerpts from the book, without the text. I would play with the scale of the images, making the landscapes large, bringing the viewer into that humbling mindset one can only experience in the expansive American West.

Reading the wall and reading a book are so different. A book is portable—it allows the viewer to relax into looking and to revisit whenever they want. Books slow you down, require time, and feel intimate. You’re in your own private world caught up in the story of words and images, whereas images on a wall need to be treated as something else. I would love to return to the Southwest to shoot a video of the landscape—something like that would great in the context of the book. It would complement it, but not mimic it.

DH: Before we wrap this up, I wanted to address your presence as the photographer. It is a constant thread throughout the book. What is your role in these stories as a maker?

TB: Simply put, my work is a visual record of a collaboration between individuals and my afterthoughts, and an attempt to be of use. My own biography often intersects with others and percolates up in ways I don’t understand until later, when the subconscious finds a voice. In retrospect, I can see the work is both mirror and window.