Located along the Black Sea coast, Sukhumi was once a popular summer holiday destination and capital of Abkhazia. In the early 1990s, the seaside city became a disputed territory, embroiled in a conflict between the newly-independent Republic of Georgia and Abkhaz and Russian forces. As a consequence of this war, 250,000 Georgians were displaced from their homes, and have not been allowed to return since.

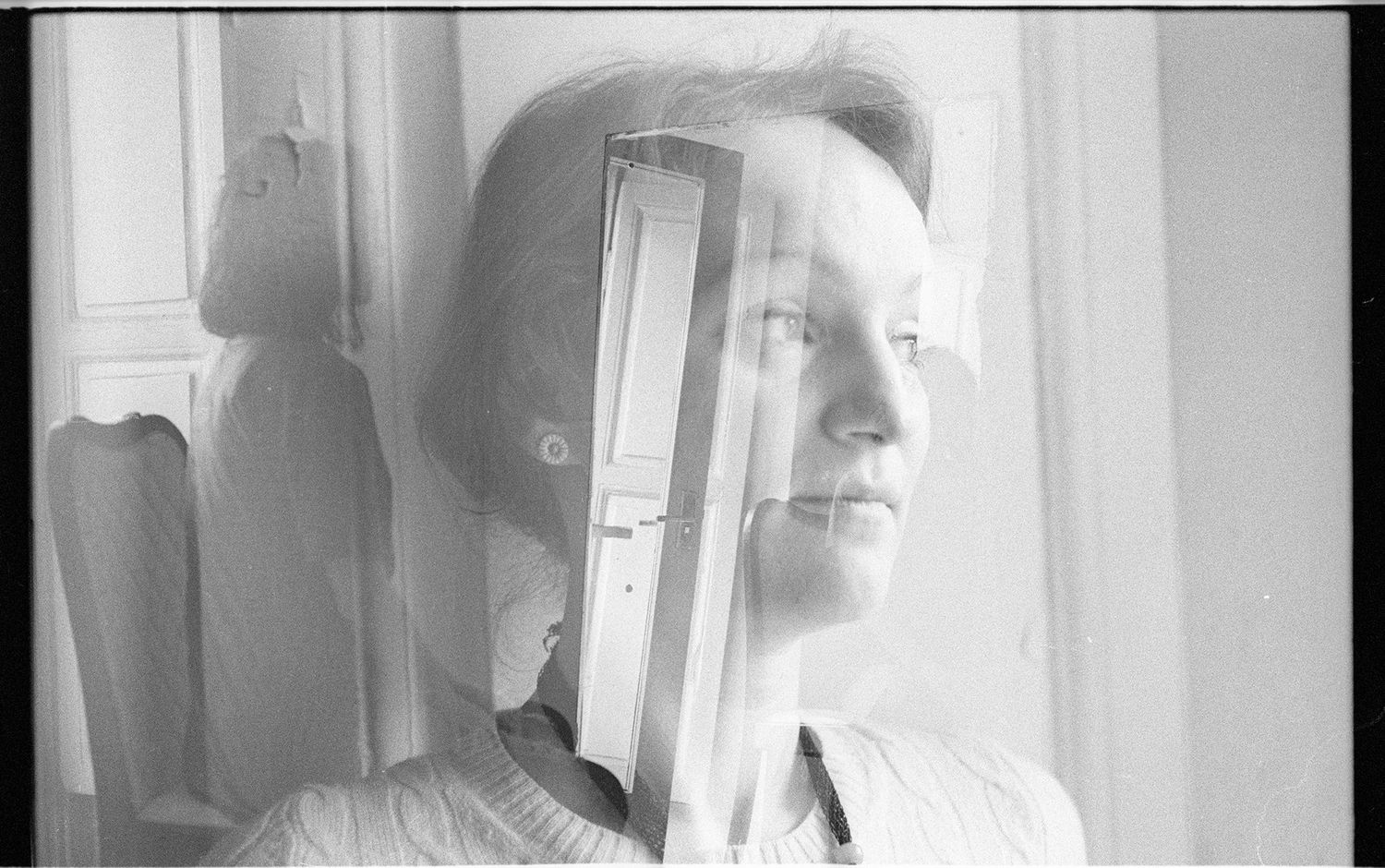

Tbilisi-based photographer Nata Sopromadze was among them. In Broken Sea, an intimate collaboration with friend and colleague Irina Sadchikova, Nata revisited her memories of her homeland. Guided by Nata’s recollections, Irina visited Sukhumi, photographing her friend’s former house and local area. She then sent the undeveloped rolls of film back to Tbilisi, where Nata photographed her daily life and that of her children, creating an imprint of her present onto the past she had to leave behind.

In this interview, the pair speak to LensCulture about meeting each other for the first time, surpassing borders through photography and uniting past and present in the double exposure.

LensCulture: You met through photography. Can you tell me a bit about how you first encountered each other and became friends?

Irina Sadchikova: I met Nata at a masterclass by Antoine D’Agata, which was part of Tbilisi Photo Festival. At first, I was deeply touched by her photos. I didn’t know Nata’s story at that time, but it was obvious that something not very pleasant had happened to her. The main theme throughout her photography dealt with variations of symbols of death—flowers on tombs, dead animals on the road, etc. I was interested in understanding what was behind it. Later, I discovered that she had had a very happy childhood in the small town of Sukhumi, close to the Black Sea.

She lived with her family in a big house with a yard, typical for these Southern regions, where kids played together. This yard was like a small model of the USSR, where people of different nationalities lived together—Georgians, Abkhazians, Russians, Ukrainians, Jews. When she was 12, the war stopped all of this, and Nata had to run away to Tbilisi with her family. They were in a rush and had to leave all of their important possessions—toys, pictures of her childhood, and a dog that she loved dearly. This story shocked me. We stayed in touch after our first meeting, and later became friends.

LC: Can you outline your individual practices as photographers? Do you have mutual interests? Would you say you use different photographic languages?

IS: I use photography to delve deeper into the theme of existentialism and the spiritual part of life. It doesn’t matter what the subject is, because the theme is always the same. We definitely have mutual interests in photography; we like the same books, the same pictures and the same photographers. We both, for example, enjoy the work of Antoine D’Agata, Alec Soth, Alex Majoli, Diana Arbus and Sally Mann. Our photographic language is similar and different at the same time. I think that Nata is more direct in her narrative—braver. She is very honest in what she is doing, opening herself up through photography. But most importantly, we like what each other does with the medium.

The way we worked with double exposure was a kind of a risk. We didn’t know what the result would be. When the film was first developed, we found that the experiment worked. The most important thing was the conceptual coincidence of the images, like the sea on fire, or my son in the background of my house’s yard. Finally, double exposure with different layers became the exact form to express memories, to unite past with present, and to break these enforced borders.

LC: Tell me about the beginnings and background of Broken Sea, and the conversation that started it all. Had this been a project you had on your mind in any other form beforehand?

IS: The beginning of the project was a coincidence, like the whole project itself. In fact, we never thought of it as a project while we were doing it. We only realized it when we started to think about making a photobook. One day I was in Tbilisi, and we were having a lunch together in a small cafe. Our normal conversation transitioned to the topic of Nata’s childhood. She once had a dream about going to Sukhumi to see her native town and house, but in reality, it isn’t possible for her to go back. Sukhumi is now part of the Republic of Abkhazia, and as a Georgian citizen it is almost impossible to access it. Coincidentally, I was planning to travel very close her native town, and proposed that I go and see it instead, as it is possible for a Russian citizen. Nata prepared a list of places that were important to her, and that’s how first I found myself in Sukhumi.

Nata Sopromadze: I often say that my photography comes from childhood memories. Memories of the war, which forced me to leave the place I was born and raised in, where I spent the happiest period of my life. People of my generation who went through that same tragedy still have an untouchable desire to get back the life that was taken from us. This feeling has lasted within me for 25 years. Somewhere, 350 km away, there is a world with locked borders for us. This dream to go back to a captured home is what transformed into the project Broken Sea.

LC: Nata, can you sketch out an impression of Abkhazia, and in particular Sukhumi, as a place,? What is your relationship to it and what are your memories of it?

NS: I was 12 when I left Sokhumi. With it, I lost my home, my friends, and my pets. My interrupted childhood stayed there. Those materialistic memories turned into dreams and, over time, Abkhazia became a mirage with many layers.

LC: And Irina, what was your relationship to the region before the project started?

IS: I had never been to Sukhumi before. I had only heard about it. When I was very small during the Soviet period, it was a resort on the Black Sea that everybody dreamed of visiting. My aunt went there and spoke about how beautiful the nature was, with its subtropical trees and flowers. In her words, it was a paradise. But after the collapse of the USSR, the war in the region started. I remember some TV broadcasts about it, when people were fighting with each other. You cold hear guns shooting, and in the background you could see the sea and some beautiful buildings that were damaged. Before my first visit, the town was a mixture of these memories in my head. Frankly speaking, I didn’t know what to expect.

LC: You speak about the idea of borders, and in some sense surpassing them through this ‘manifesto’ formed through photography. Can you elaborate on the kinds of borders you speak of, and tell me a bit about how you came to the idea of this collaborative way of working?

IS: After my first visit to Sukhumi, when I made pictures of Nata’s favorite places in town, I suddenly realized that by using photography, we could subvert what is made impossible by borders—photography helped destroy them. This is our manifesto: we believe that people should have the possibility to visit the places where they were once happy. Borders, restrictions and limitations shouldn’t exist in the 21st century. Quite often, when we explain the idea of the project, people find that they have something similar going on in their lives. They have places that they can’t visit for all sorts of reasons. But it’s not just about physical borders—it’s also about mental borders. For me, this project was about helping my friend Nata unite herself with this town, to return her in her childhood, and to start a new page in her life without looking back.

LC: Nata, tell me about the places you asked Irina to photograph. What kinds of memories did they hold for you?

NS: They were the places that I remembered best, and where I spent most of my time, like the botanical gardens near my home, Sukhumi beach, Dendro Park, the school yard, some streets. But the photos I was waiting for the most were of my home, which Irina couldn’t get because the house belongs to other people now.

LC: Irina, tell me about the process of discovering Sukhumi in this way. Can you describe what is was like to act as a proxy set of eyes?

IS: It was a very unusual experience to be in that place for the first time, looking at it through someone else’s eyes. From the very beginning, I felt the support of the town in the fulfillment of my task. Every time I needed something, or a problem materialized, it was solved—an unknown person I met on the road would explain something missing to me, or open the door to the places I was looking for. At a certain point, I started to understand that I was like a Georgian girl in this small town. It was a very strange feeling. My eyes were constantly trying to catch something that was beautiful—something nice in Nata’s childhood. Something that does not exist anymore.

LC: Though there is a quietness and softness to the images in Sukhumi, the second layer adds a tension and weight that speaks to the experience of displacement. Can you talk a bit about the layer of images that came after the initial photographs?

IS: The first layer of each picture was made in Sukhumi. The second layer was made by Nata in Tbilisi. When Nata received the film from me, the only thing she knew about it was that it came from Sukhumi. Similarly, I didn’t know what her plans were for the second layer. There was total freedom for both of us while making these pictures. The final photographs are the result of total coincidence. It’s almost as if there was a third person in the project who finally piece it all together. There were a lot of strange, almost mystical things that occurred. Once, when I was in Sukhumi, Nata had a dream about her native house being full of cats. Later, I was really shocked when I heard that one of her old neighbors had a lot of cats that often walked in the yard of Nata’s house.

NS: For the second layer, I wanted to capture the impressions I had through the post-war period. They are still alive and I don’t want them to disappear. This second layer is my second half, and is more fraught and intense—radically different from the Sokhumi first layer.

LC: This intervention of the double exposure adds another layer to this collaboration. It literally inscribes two temporalities—two spaces into each frame. It’s a gesture that rejects any one certainty or static narrative. Tell me about the double exposure, and what it represents for you both.

IS: In our situation, double exposure was a very natural choice to unite someone with a space that they can’t access. It represents the possibility of moving under the established borders. Double exposure helps create another reality that ignores the rules of the physical world, instead creating something new. It helped reunite Nata with her native town, Sukhumi.

There is also one important picture, which is of particular importance on a personal level. Maybe we should have done the entire project just to end up with this one. On the first layer of the image, there is the yard with Nata’s house, and on the second layer is an image of her son. He had never been to this place, and had never seen this house, which was built by his great grandfather. But in the picture, they are together. It gives some hope for the future.

NS: The way we worked with double exposure was a kind of a risk. We didn’t know what the result would be. When the film was first developed, we found that the experiment worked. The most important thing was the conceptual coincidence of the images, like the sea on fire, or my son in the background of my house’s yard. Finally, double exposure with different layers became the exact form to express memories, to unite past with present, and to break these enforced borders.

—Interview by Sophie Wright