In March 2016, the borders surrounding Greece closed in the wake of the EU-Turkey deal, leaving more than sixty thousand individuals seeking refuge from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Eritrea, Pakistan and Palestine, among others, suspended in untethered limbo. Unable to continue their journeys to settled independence, most of these refugees still remain in Greece, awaiting asylum applications or pursuing illegal routes in central Europe, all without documents, accommodation or financial stability. Due to the Greek government’s persistent economic stress, as well as petty politics across the EU, official response to this disastrous situation has been virtually nonexistent. Refugees barely remain afloat, building communities of their own from scratch, often in abandoned buildings and structures across the country.

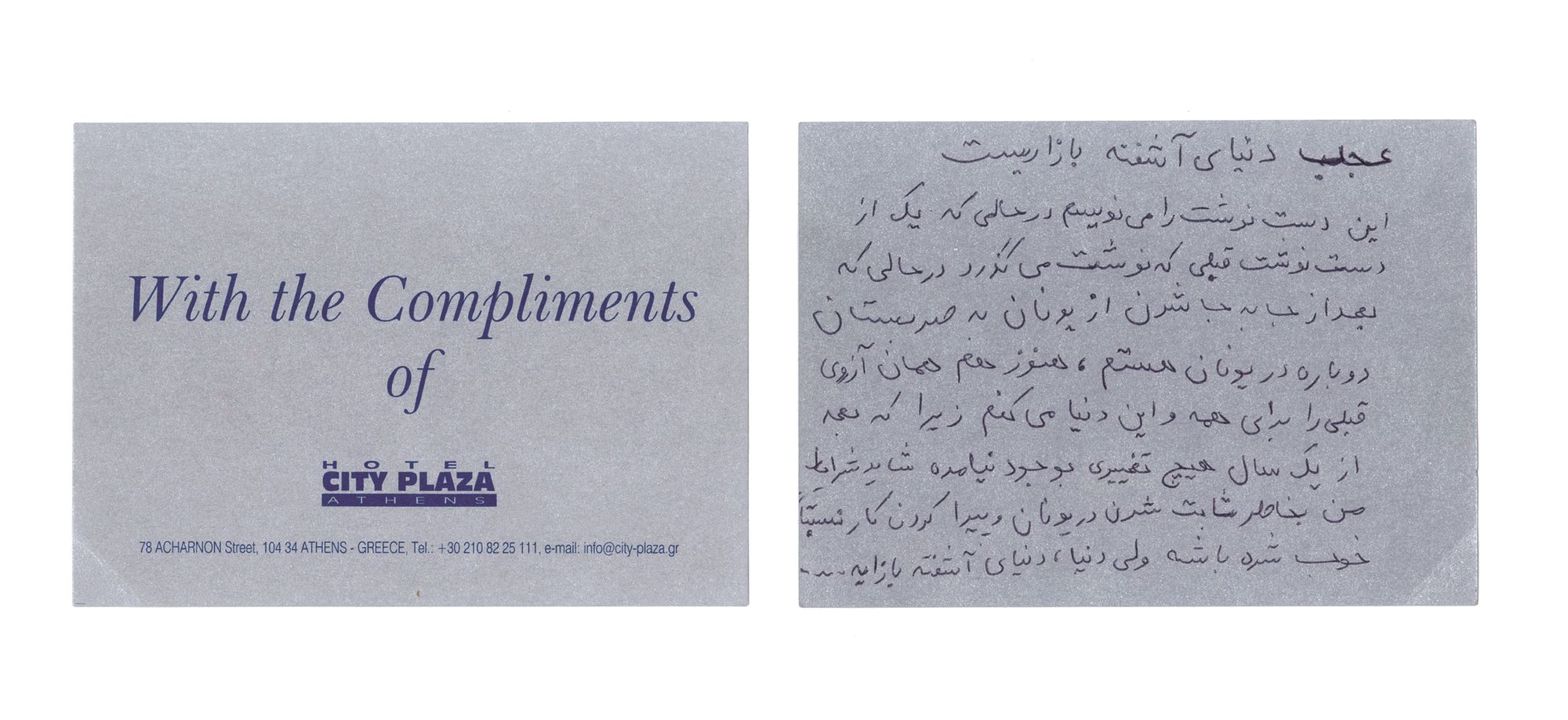

While pursuing a project about bailout loans in Greece in 2016, documentarian Andrew O’Carroll heard about the Hotel City Plaza, a squat operating in solidarity to support unintentionally trapped refugees in Greece. A friend of O’Carroll’s found some old compliment slips in the space, from when the Hotel was operating in its original capacity. Using these slips and other scraps of paper, O’Carroll started asking a number of the squatters to record messages about how they were feeling on the cards—anything from a letter to a friend to a complaint, a hope or experience, and even a song. In addition to collecting these written records, O’Carroll began to document daily life in the hotel with his camera. “The portraits ended up being quite compelling, and were even more successful when paired with the compliments slips,” he explains.

O’Carroll spent a month making the work, befriending residents of the squat and immersing himself in their daily lives. “Their network is large, but it isn’t overly-publicized for political and safety reasons,” he explains. “I slowly met more and more people who introduced me to other squats. It quickly became apparent that the Hotel City Plaza was part of a bigger narrative of citizens, even those who currently experience difficulties from the economic crisis, taking action and suggesting solutions where the government and traditional structures are failing.”

The images that make up the series Take me to my home work to convey the atmosphere of the Hotel City Plaza, and the people who carry out their lives within its walls. In each photograph, the building acts as a protagonist as much as the human subjects, with its unassuming textiles and industrial windows—a strange mix of familiar hotel decor and the warmth of personal space. For O’Carroll, this nuanced space is a reflection of the gray area that the refugees experience on a daily basis. Each moment is spent in pursuit of their freedom and independence, but at the same time, the Hotel has become their home, and its walls filled with a community that is hard to leave. Associations are made between people and place in the captions, and O’Carroll weaves the images together with portraits and scans of the subjects’ messages to create a dynamic project that works to reveal the intricacies of the stories his images want to tell.

“I always remember attending a final goodbye party for Abdollah, a young boy from Syria who was leaving for asylum in Germany after months of waiting for approval,” O’Carroll reflects. “Life in the squats and in Athens marked a period of growth and development for Abdollah, and he had carved out a lot of freedom and responsibilities for himself. I sat with a group of his friends – 15- and 16-year-olds – on top of a mountain a few hours before his flight, singing goodbye songs and drinking beer. They were a tight community, but had developed in a situation that was never intended to be permanent.”

Stories like Abdollah’s are alluded to throughout O’Carroll’s work, and the photographer hopes to inform a new audience about the refugee situation in Greece, as well as all over the world. “I have not fully understood who my audience is yet,” he explains. “I hope the work respects the nuance of the events while being engaging, unique and intimate. I know it is unrealistic to expect the work to achieve certain things, but I still hope it stands as a subjective and respectful record of an important time of change.” O’Carroll is careful to posit his work as something adjacent to activism, despite his understanding of the limitations of the medium and his own experience. He reflects, “At the end of the day, I do want to make work that will encourage political dialogue, and I would like to keep pushing my work, thinking in engaged ways about how it can be presented.”