3,000-Year-Old Tomb of King Tut Finally Restored

Conservators have finally completed a decade-long restoration of the tomb of King Tutankhamun in Egypt.

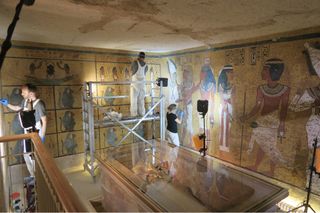

The project — carried out by the Los Angeles-based Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities — involved stabilizing the wall paintings that decorated the 3,000-year-old tomb, as well as adding features like new barriers and a new ventilation system that would reduce damage to the site in the future.

"Conservation and preservation is important for the future and for this heritage and this great civilization to live forever," Zahi Hawass, Egyptologist and former minister of State for Antiquities in Egypt, said in a statement.

Tutankhamun was born during Egypt's New Kingdom, around 1341 B.C. Sometimes called the boy king, he began his rule at age 9, and died suddenly in his late teens. [In Photos: The Life and Death of King Tut]

Tut's tomb became world famous in 1922, when British Egyptologist Howard Carter found the site in pristine condition. While many other royal tombs in Egypt's Valley of the Kings had been pilfered in antiquity, Tutankhamun's burial chamber was discovered intact, thanks to mud and rocks that blocked the entrance.

Carter's team spent 10 years removing artifacts from the richly packed tomb. After their investigation, the site became a major tourist attraction.

But visitors bring dust as well as changes in humidity and carbon dioxide levels that have threatened the fragile environment inside the burial chamber.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The restoration included an investigation of mysterious brown spots that were feared to be growing like a fungus in the wall paintings.

Conservators confirmed that the spots were microbes, but they were long dead, and had not in fact spread since Carter opened the tomb in 1922. What's more, the microbes had already grown into the paint layer, so they couldn't be removed from the wall paintings without damaging the artwork.

The tomb — open to visitors through much of the conservation — still contains some of its original artifacts, including the mummy of Tutankhamun.

"All of these objects have to be protected because they are the results of an excavation that, by the very definition of archaeology, has destroyed an archaeological site in the process of digging it," said Egyptologist Kent Weeks in a video about the restoration released by the Getty Conservation Institute. He added that the conservators might be the most important players on a modern archaeological excavation in Egypt.

"Objects that we get out of that site are only as useful to us as the context that we have recorded them having been found in."

- Image Gallery: Egypt's Valley of the Kings

- Photos: Ancient Egyptian General's Tomb Discovered in Saqqara

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Original article on Live Science.