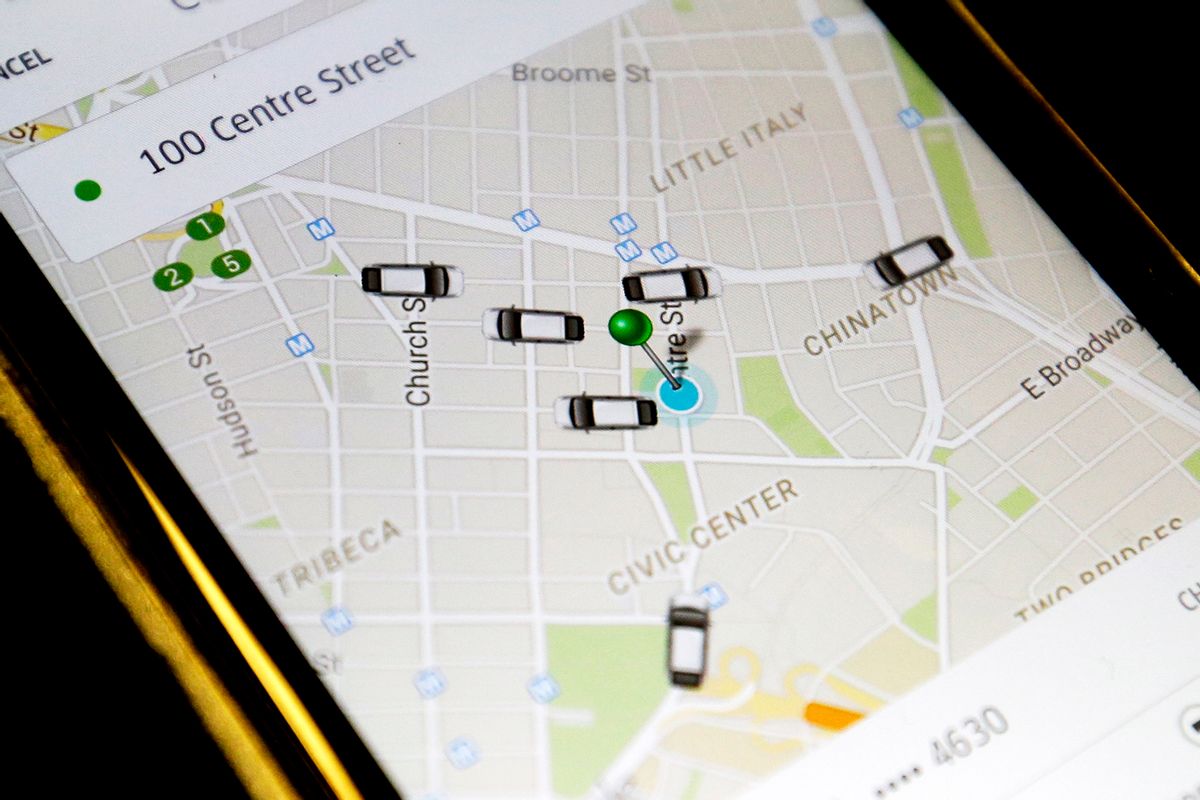

Call it the “reclassification war”: the fight between the big gig economy companies who want to retain their right to keep on as much cheap contract labor as possible, and labor laws that stipulate that a company’s core workers have to be marked as employees, not freelancers. You’ve seen the reclassification war in action most visibly in companies like Uber, AirBnb and Lyft: in all three of those cases, the work of contractors makes these platforms hum.

Yet there’s good reason to want to be a real employee: the costs of the necessary things needed to do one's job — things like gas, maintenance and insurance in the case of, say, an Uber driver — fall on the employer, not the employee. Currently, contractors are responsible for buying their own gas and covering maintenance, and are not even guaranteed minimum wage if demand is low for rides. Of course, minimum wage laws come into play when you’re an employee, too — not to mention other legally stipulated perks, such as healthcare, certain civil rights and fair hiring protections, and other benefits depending on the jurisdiction.

The line between contractor and employee is not as blurry as it seems — it’s just often unenforced. A 2018 California State Superior Court ruling decreed that a company can only hire contractors if they “[perform] work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.” That seems like a blow to contractor-dependent companies like Uber and Lyft: if they consider themselves essentially taxi companies, then their contract-worker drivers are certainly not “outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business,” much as Lyft and Uber brass would prefer to believe otherwise.

Yet little has changed in California since that Superior Court ruling: the gig-ification of the economy continues apace, particularly among Silicon Valley’s many startups. Many, self included, have called for contract-heavy companies Uber and Lyft to convert to worker cooperatives or for alternative worker cooperatives to form in their wake.

Companies like AirBnb, Twitter, Facebook, Uber and Lyft epitomize one of the most glaring contradictions of the distributed labor model innate to all these Silicon Valley platforms: in each case, the bulk of the labor that makes them function (beyond the programming of the platform itself) is done either by contractors (Uber, AirBnb) or by users for free (social media). Doesn't it make more sense to cut out the middleman and let the users/contractors own the fruits of what they produce?

This proposal is less complicated logistically than the status quo, and would remove some of the major problems of relying on contractor armies — namely, the high turnover rates and low pay. Few Uber or Lyft drivers last more than a year, meaning the churn is exceedingly high, and the companies must constantly recruit. Similarly, worker co-op schemes would help our increasingly unequal country fight its income inequality problem and rebuild the middle-class: as economist Richard D. Wolff and others have noted, employee-owned enterprises are one of the best ways to redistribute wealth back to the non-rich. The movement to do so within these tech companies is known as “platform cooperativism” — and while the major shareholders and C-suite aren’t going to be keen on such a scheme as it would reduce their power, they are keen on solving the turnover crisis without actually doing anything too drastic to redistribute wealth.

Enter the stock grant.

Stock grants are a normal perk for many white-collar, and even some blue-collar employees at many companies. Quite simply, they go like this: employees, after a period of employment, may earn shares in the company they work for. Such schemes make said employees feel like they have a greater stake in the day-to-day success of their company, even if the number of shares they own is technically minuscule compared to the major investors and people at the top.

Now, the San Francisco Chronicle reports that some tech companies, namely AirBnb and Uber, want to grant shares to their contractors. Uber issued a comment to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which you can read here, asking them for permission. The reason for the SEC request is that it turns out giving equity to contractors is not quite legal yet.

The cynical view on the decision to offer equity to gig economy contractors is that it is, to paraphrase Rosa Luxemburg, akin to reformism over revolution — meaning, by enacting a minor policy reform in offering equity to contractors, companies like Uber and Airbnb don’t fundamentally solve the innate inequalities and exploitations that their business models generate. Rather, they merely stave off future upsets to their business model, particularly the looming prospect faced by Uber and Lyft that they might literally run out of potential drivers as the supply of interested workers decreases in a labor market with historically low unemployment.

The bottom line is, stock options for contractors might seem like a convenient short-term step to remunerating contract workers better, something that we’re all in favor of. But such an act doesn’t overcome the fundamental structural problems with contract labor, nor the small exploitations suffered by contract workers who have no guaranteed pay, benefits or job security. As such, it comes off as more of a recruiting and PR tactic than genuine Silicon Valley reform.

Shares