Christianity and sexuality rarely make easy partners. For many of us, we grow up with the constant message that we must be pure not just of body but mind. That God can hear our lustful thoughts. That to explore or even contemplate our sexuality is sinful. Oh, and that then when you marry the person of the opposite sex person with whom you are going to reproduce, it's a beautiful blessing from the Lord.

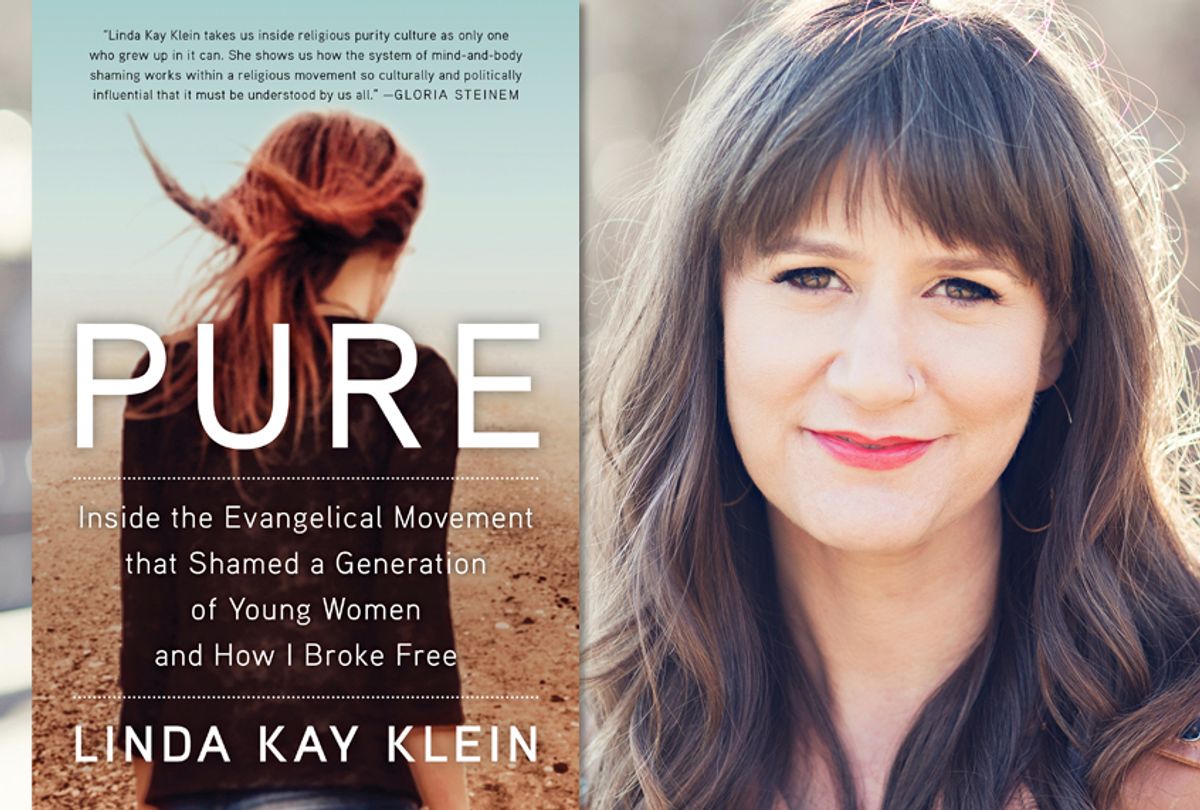

No wonder so many of us grow up confused and ashamed. Yet the values of Christianity — of humility, love and compassion — remain there in the mix as well. For author Linda Kay Klein, finding her way out of the purity movement that permeated her evangelical upbringing and moving toward a different kind of faith was a difficult journey. In her new memoir "Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free," she reveals her complicated past, and the lucrative business of keeping kids chaste — from abstinence sex education to purity rings.

The book could not have arrived at a more apt moment in my own life — I recently walked out on the Catholicism I've practiced my entire life. But to the confusion and dismay of my atheist friends, I'm not giving up on God. I'm just still on shaky legs as I figure out where I'm going next. So I talked via phone recently to Klein about her own journey, and when happens when we ditch a church but not the faith.

"When I left evangelical Christianity," Klein said, "I was under the impression that I would no longer have access to God, because that's what I'd been taught. For a long time after leaving evangelical Christianity, I kept having these yearnings to pray. I wouldn't allow myself. I would feel that you have to believe to be allowed to do this. It took me a long time to give myself permission to start to come back into relationship with God."

Now, she says, "The spiritual part of my life, is just a fact of my life. There's just no choosing it. It just is. The community part, the institution of the church part, has been a much more complicated journey."

Throughout "Pure," Klein draws on her own experiences of trying to stay morally upstanding and self-sacrificing, sometimes to the detriment of her own health. She also examines the deeply conflicting messages organized religion frequently provides us: Sex is bad unless it's good; God loves you unconditionally unless you do something — even unwittingly — that condemns you to eternal punishment. Klein said that feels like "a form of hubris" to her.

"We think that we can tell anybody whether or not they are allowed to be a Christian, or whether or not they are allowed to be in relationship with God," she said. "What do we know? What do we think we are, that we can tell somebody else what God thinks and feels about them? That our perception of God's feelings toward them are more important than their own relationship with God?"

It's a whole other level of complication when we're trying to raise our kids in faith. As my daughters went through Sunday school, they rarely received any guidance beyond a strong imperative to dress modestly. We're fortunate that they can talk with their family and have public schools with strong sex ed programs, because if we'd left it to the church, it would have begun and ended with "Don't."

"There are no specifics about what makes you impure," said Klein. "The reason is because ultimately, it's the community's perception that matters more than anything else. It depends on whether you happen to interact with someone who believes that as long as you don't have sex before marriage, you're pure, or you interact with somebody who thinks that emotional intimacy with someone of the opposite sex is enough to deem you impure."

"Ultimately, you're constantly in this state of anxiety as other people define whether or not you're pure, based on their version of what the rules are," she added. "Then you add in what the community considers to be entirely within your control, which is the thoughts and feelings of men in the community toward you."

Yeah, that. The insistent sexualization of girls and women from an early age sends a very clear message — to boys, too — about who the gatekeepers of purity are supposed to be. Purity culture, says Klein, really ends up objectifying girls.

"You're teaching them that their body is the most important thing about them," she said. "You're not seen as a student in the room. Even when you're in a place where you're trying to build your knowledge, trying to grow into a wiser and more knowledgeable person, still, even here you're being told, 'Yes, but the end of the day, you're a sexual object.'"

This burden becomes even more acutely felt when a person is the victim of sexual assault, a stigma that abduction and rape survivor Elizabeth Smart has candidly spoken about.

"Essentially, the purity ethic is one man, one woman in marriage forever," said Klein. "That purity ethic is used to assess everything. Consent is not part of the purity ethic because the church has almost nothing to say about sexual abuse or violence. The result is that sexual abuse and violence gets assessed by the purity ethic just like everything else does. Did it happen between one man and one woman in marriage forever? Yes? Then it's fine. That's not rape. Did it happen outside of one woman, one man in marriage forever? Then it is sexual impurity. Because our ethic doesn't have anything about consent. We subconsciously assess everything based on the one ethic that we have."

That ethic also doesn't allow for different forms of sexual orientation and gender identity.

"It's generally presented as either sin or psychosis," said Klein. "You see that a lot in the LGBTQ community where people are told, 'Let's talk about your relationship with your parents. What did your mom do that screwed you up? What did your dad do that screwed you up? What exposure to sexual content did you have as a child that screwed you up? What is it that has made you a broken now?' I think a lot of people, if they don't feel like it's their sin that's the problem, they feel like it's something else that's that deep-seated and wrong."

Even if you've had a presumably trauma-free, chaste, exclusively heterosexual existence up to your wedding night, the pitfalls are still plentiful. Healthy, fulfilling sexuality doesn't magically kick in the minute you put a ring on it. In marriage, Klein says, a new set of counter expectations for women crop up.

"You are expected to pleasure your husband. This is one of those things that is really talked about a lot in evangelical culture. You're expected to be a lamb outside of your marriage bed and you're expected be a tiger in it," she said. "But you've never been taught to roar. Ultimately, we're setting people up for failure."

"I've heard many cases where the pastor will say, 'Well, the equation is if you're non-sexual before marriage, you'll have a blissful sexual relationship in marriage. What did you do wrong before you got married? Did you ever masturbate? Did you ever make out with anyone? Did you have sexual thoughts or feelings that you need to confess?'" she continued. "Obviously, the problem must be that you didn't fulfill your end of the equation. It's just a way to offend someone deeper and deeper down that shame spiral."

It's a neat institutional trick, and the ultimate power move. And the consequence of the evangelical culture's obsession with purity, Klein says, is the amount of control it places over people's lives — especially women and girls.

"If you can control somebody's sexuality, you have a deep amount control over them," she said.

She adds, "I think it's very difficult for people not to come to the conclusion that your sexual purity is essentially the same thing as your salvation when you're hearing these messages all the time. There are a lot of people who I've spoken to people who have said, 'I really feel like the most important thing that I can do to express my Christianity is not have sex.' Which is so sad, because for me Christianity is about so many beautiful and important things that are so much more important than the shame spiral that I was going down to try to protect my purity."

And this is where Klein and I find ourselves, even now, in a faith system that has can be so great when it's detached from its hangups.

"This hyper focus on sexuality takes up way too much air time and prevents us from doing the deep exploration around topics that we need to be exploring. It's about love," Klein said, "and it's about how we treat one another. It's about justice. It's about so many things that are valuable, and that we need to be engaging with on a deep level."

Shares