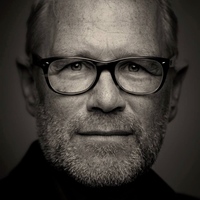

Roy Kahmann’s diverse professional endeavors — including a respected photography gallery in Amsterdam, an authoritative photography magazine, and an international photo fair — were catalyzed by his first experiences with photography as a young designer. While working on Ed van der Elsken’s seminal photobook, Amsterdam, he became fascinated with the medium, particularly black and white imagery. This early interest led him to found Kahmann Gallery in 2005. Today, the gallery represents the work of almost 30 national and international photographers. Kahmann also founded GUP (Guide to Unique Photography) Magazine in the same year, a quarterly international publication dedicated to photography.

We are thrilled that Kahmann has agreed to be on this year’s jury for the LensCulture Emerging Talent Awards 2018. I reached out to Kahmann for a conversation about how his interest in photography began, why he’s drawn to black and white imagery, and what inspired him to start GUP Magazine, a publication that prioritizes emerging photographic artists.

—Cat Lachowskyj

LensCulture: Tell me a bit about how you first became interested in photography. Were you a photographer yourself, or were you working with the medium in a different way?

Roy Kahmann: In the late 1970s, I had my first job as a junior designer at the international company Total Design, where I worked with renowned graphic designer Anthon Beeke on Ed van der Elsken’s book Amsterdam. Many of the photographs passed through my hands for the layout, and in this way, van der Elsken taught me what makes a good photo, like the crop and depth-of-field, as well as what constitutes the strength of a successful photo, at least in his eyes.

LC: What was the first photograph you acquired, either as a gift or by purchasing it? How did it impact the course of your subsequent collecting?

RK: After almost a year after working on the book, I bought my first photo: an Ed van der Elsken. I also began tearing pictures out of magazines and framing them. Throughout my jobs as a designer and art director, I worked with various photographers whose pieces I would then buy. Our house was filled with frames! After that, I gradually started to replace the torn out pictures with real prints. I mostly focused on Dutch photographers to start with, but in the early ‘90s I began including international names. My serious collecting started around then, by visiting galleries and auction houses in New York. Our collection—which I built together with my wife, Lindy Hering—consists of about 95% black and white prints. The reason behind this is that I acquire pieces intuitively, and they need to have a connection with the rest of my collection. I’ve bought works dating from just after World War II to contemporary work, and because of the lack of color, they have a certain timeless quality to them, and somehow fit together with one another.

LC: What is it about the medium of photography that specifically continues to interest and inspire you? How does this inform which artists you choose to work with at the gallery?

RK: Photography is the medium that first put me in touch with art, but my interest in it also has to do with its connection to graphic design and books. I used photography in my own designs, so I was working with it every day. I grew so familiar with it that it became the only logical art form for me to work with. For the gallery, I look for artists who interest or surprise me, but I’m also drawn to pieces that I would like to have for myself. When you have that feeling, it’s easier to convince others of their value too. Timeless subject matter plays a huge part in this. Whether it’s black and white or in color isn’t of great importance. The group of photographers that we represent at the gallery are broad and diverse, and they explore the boundaries of what is considered photography, either digitally or manually.

LC: You have taken your own interest in photography and transformed it into an expansive network for helping others foster their interest in the medium as well. What excites you the most about working with and helping others find the perfect piece for their own collection?

RK: Our goal with the gallery is to heighten the appreciation for photography as an art form and have the audience for the medium grow larger and larger, so it’s very exciting when you find someone who shares your interest and wants to learn more about it, and who wants to foster an artist’s career by buying their pieces, or acquiring a piece of history in the form of a vintage print.

LC: How did GUP Magazine come about? Why were you compelled to start this publication?

RK: We started the magazine around 15 years ago with the purpose of bringing more attention to emerging photographers, and it evolved into its own entity with an entirely independent editorial staff. I’m quite proud when people don’t realize I started it, because it means that it has become something that stands on its own. It’s become a platform for emerging photographers, but it’s also a platform for talking about themes within the medium in depth. Another point of pride with GUP was when I was told that the Rijksmuseum has been collecting the issues from the start.

LC: How have you seen photography change throughout the decades you’ve been interested in the field? What elements have you seen prevail, and what are some trends you have seen fizzle out?

RK: I’ve definitely seen the digital revolution change the medium in a big way. Seeing how extremely sophisticated digital cameras have become, and also how digital prints have come to rival analogue prints has been huge. When I started collecting, photography really was a craft that was executed by a small group of trained experts. Now, anyone can be a photographer, with smartphone apps and the amazing quality of affordable cameras. Within the art photography market, I’ve seen the distinct categories disappear. A documentary or fashion photographer can now also make art photography, which was not necessarily the case back in the day. The commercial photographers of yore are now seen as artists, with matching prices at galleries and auctions.

LC: What are some factors you think define strong work from emerging talent? What do you look for in emerging talent?

RK: A signature style, authenticity, a good work mentality, and of course, having the eye. It’s not just about looking for certain factors—it’s having a gut feeling about someone. Sometimes this can fail, but most of the time the result is something great.

Editors’ note: Roy Kahmann will be judging entries to the LensCulture Emerging Talent Awards 2018—enter now for your chance to get your work in front of Becker and the rest of the world-class jury. There are also a host of other great awards. You can find out more about the competition on its Call for Entries.