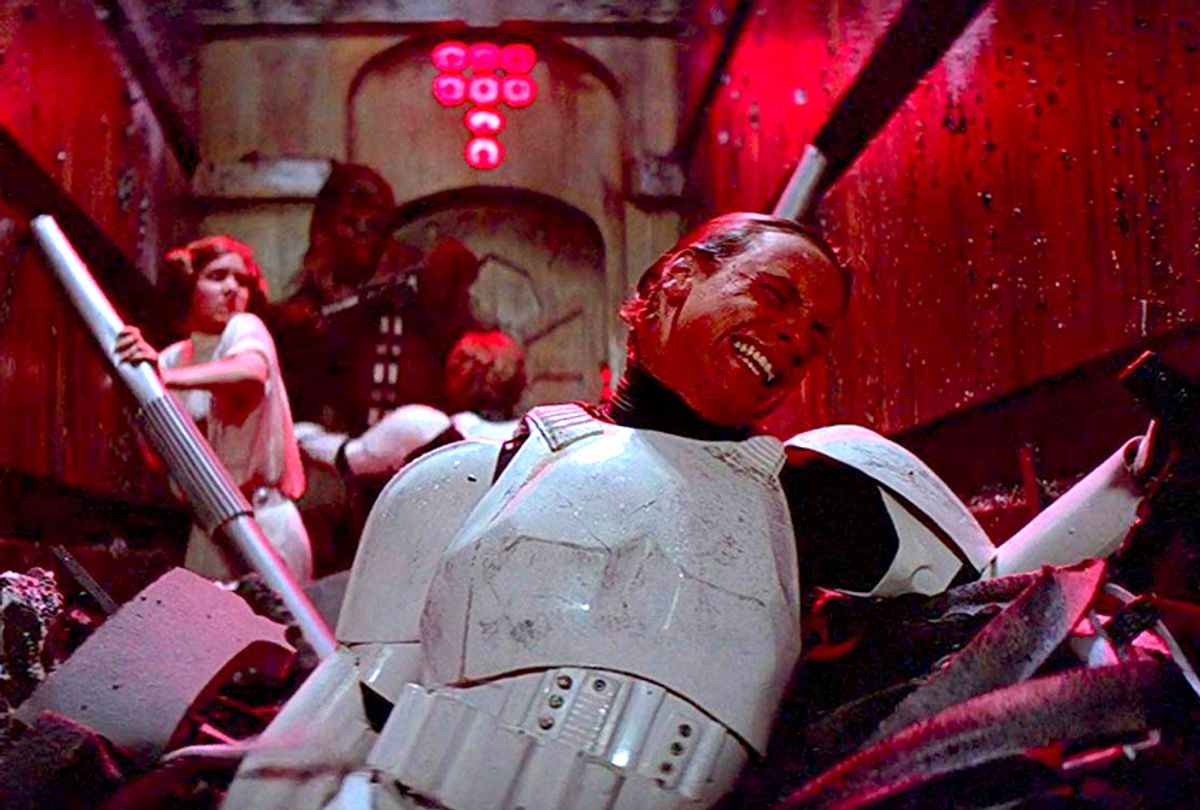

Dirt, trash, scuffs, scratches. The desert-battered surface of Luke’s landspeeder, and the worn, washed-out fabric of his farmer’s clothes, bound and belted against the sand. Han Solo’s outfit, a collage of trophies and souvenirs from a past on both sides of the law, from the Imperial Academy to the Corellian spacers, and his customized "piece of junk" pirate ship. This is the aesthetic of the Rebels. A make-do-and-mend approach, in a time of galactic war. An attitude of improvisation, of rolling with the punches, of striking, scattering and moving on. The Rebels are freedom fighters, or terrorists, depending on your point of view: they are potentially everywhere, and hard to pin down. Leia can give up the location of a previous base on Dantooine, knowing the Empire will find only deserted buildings and footprints. They establish a new headquarters on the moon of Yavin, and at the start of the next film have not only relocated to the ice planet Hoth, but are ready to evacuate again. In "The Empire Strikes Back," the Falcon evades the Imperials by waiting until a Star Destroyer dumps its garbage, and floating out with the refuse; an echo of their previous strategy in "Star Wars," when Leia blasts a hole in the wall of a pristine Death Star corridor and the rescue team follows her into a trash compactor. The Rebels not only discover the rubbish that the Imperials’ sleek white surfaces usually keep hidden; they immerse themselves in it and escape by hiding in their enemies’ waste, knowing the Empire will, primly, never look at its own dirt.

A character’s attitude towards trash, dirt and junk defines their place on either side of the film’s key opposition between rough, improvisational energy and cold, clean formality, and the distinction is not quite so simple as Rebel versus Empire. See Threepio "can’t abide those Jawas. Disgusting creatures," and Leia scorns the bolted-together hulk of the Falcon: "You came in that thing? You’re braver than I thought." Some of this disdain can be put down to competitive banter between the kids and Han Solo – Luke calls the Falcon a "piece of junk" because Solo has just humiliated him in the cantina, and Solo’s blustering mockery of Leia ("The garbage chute, what a really wonderful idea! What an incredible smell you’ve discovered …") is part of their ongoing, aggressive flirtation.

However, Leia and Threepio, despite their alliance with the Rebels, are not from the same sphere as Han and Luke, and this difference is expressed in their appearance and manner. Leia is a diplomat and adopted into the royalty of Alderaan, a peaceful and wealthy society; Threepio is a protocol droid on a consular ship, under the charge of an Alderaanian captain. Both characters, although Leia is secretly engaged in the overthrow of the Empire and Threepio has little understanding of his own position or the surrounding conflict, belong to the culture of the old Republic – a world of moneyed elegance, poise and etiquette – rather than the rougher world of Tatooine homesteads and Corellian pirates. Luke and his uncle, after all, are accustomed to buying their droids second-hand from Jawa junk merchants.

Luke and Han, making their way as a farmboy and smuggler respectively in Tatooine’s dusty culture, have no political engagement with the Rebel Alliance until later in the story – initially, Luke just wants to get off-world through the Academy, and tells Kenobi he can’t get involved in any galactic struggle, while Solo simply wants to clear his debts – but both have the instinctive hatred for the Empire born from the experience of a colonized, brutally policed people, rather than based on principle in an Alderaanian ivory tower. Luke exclaims ‘it’s not as if I like the Empire, I hate it’, and Solo, who has just lost a hold full of spice and gained a price on his head because of an Imperial boarding party, lies automatically to the cantina stormtroopers, and shoots them dead without hesitation. Han and Luke begin the story as rebels by nature, rather than by conscious choice.

By contrast, Leia’s mannered response to her capture by the Empire – "I should have expected to find you holding Vader’s leash. I recognized your foul stench when I was brought on board" – is in keeping with the stilted conventions and delivery of Queen Amidala and the Jedi, in the prequel trilogy’s Republican society, while Threepio’s easily smudged gold plate makes him suited to Alderaanian palaces and clinical consular ships rather than farms and cantinas. Indeed, Threepio is redundant on Tatooine, and unnecessary, even offensive to its locals. Luke’s Uncle Owen, a no-nonsense farmer, remarks disparagingly that he has no need for a protocol droid, while Obi-Wan, living quietly in a desert hut, can’t remember ever owning a droid. The Mos Eisley barman even throws him out; he accepts hammerheads and walrus men, but not Threepio’s kind. In Luke’s first appearance, a scene deleted from the final cut, he owns a Tatooine-style robot – a primitive device called Treadwell, little more than a stick on wheels and light years away from the gleaming, humanoid Threepio. Threepio, cast out of his spacecraft into the desert, is not just on the wrong planet, but in the wrong film; he is a "Metropolis" (1927) robot in hopeless exile from the city, and wandering into "The Searchers" or "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962).

Both Leia and Threepio, tellingly, are at home on the Death Star. Leia is undaunted by Tarkin and Vader, exchanging cold insults with her enemies, and even in prison, fits the clean white interior of the Imperial environment. Threepio just becomes another Death Star droid, and unlike Han and Luke, can talk plausibly to stormtroopers without any disguise or play-acting. On the other side of the conflict, the sandtroopers of Tatooine have adopted a customized uniform and trained native desert lizards, the Dewbacks, as police mounts; their white armor is scored and grubby with sand. They may not be a welcome presence in Mos Eisley, but they fit into the battered, improvisational milieu, just as Han Solo’s antagonist Boba Fett, the bounty hunter with a uniform modified by trophies and scars, is his counterpart rather than his opposite. The real opposition between the two key aesthetics of "Star Wars" – warm, rough creativity and cold, formal surface – is represented by Solo and Vader: they confront each other only once, at the precise middle point of the trilogy, in a Bespin dining room during "The Empire Strikes Back." The moment presents another clash between different styles, between two of Lucas’s borrowed genres – the dark-casqued samurai facing the cowboy – and offers a far more shocking contrast than the confrontation between Vader and Leia as political foes in the previous film, or, in the next film, between Vader and Luke as dueling Jedi.

Already, then, we can see that the fable of "Star Wars" allows for considerable ambiguity and movement between its polar oppositions, as signified through the relationship between two aesthetics: rough-edged versus smooth surface, raw energy versus order, and at its most basic, dirty versus clean. The narrative arc of the trilogy includes Threepio’s loosening up until he can tell stories in "Return of the Jedi" and more significantly, Vader’s trajectory towards his battered and burned redemption while Luke, more controlled, hard-edged and formal – with a mechanical hand under his black leather glove comes dangerously close to replacing his father as the Emperor’s soldier. Of course Leia and Han compromise into a couple, with him accepting the need for discipline and responsibility, and her becoming less rigid, more playful.

Even within the shorter story of "Star Wars" itself, Han accepts a role within the Rebel order, with everything that implies – the rituals of the Rebel Alliance are inherited from the old Republic, from Alderaanian custom, and as we shall see, are disconcertingly similar to those of the Empire – while Leia becomes more of a sassy wisecracker after joining Luke and Han’s gang, most obviously when she improvises a route "into the garbage chute, flyboy."

Shares