Photographer Dorothea Lange is a seminal figure in both the history of social documentary photography and the historical progression of photography as a medium. Most individuals encounter Lange through her iconic image Migrant Mother, a photograph of Florence Owens Thompson taken in Nipomo, California at the height of the Great Depression in 1936. The contemplative mother, with her hand grazing her cheek, looks into the distance past Lange’s lens while her three children cling to and crawl up her body, their faces turned from the camera. Since it was first taken, the image has become a pervasive symbol of the Depression, and in particular represents the mass migration of Americans from the Midwestern states to California that resulted from the catastrophic economic decline.

Regarding Lange’s legacy, associations with such an iconic image have simultaneously been a blessing and a curse. While the photographer’s name remains a bolded marker in the history of the medium, her career is often overshadowed by the single photograph, leaving far less room for knowledge of her greater oeuvre and impressive pursuits. Broadening Lange’s narrative and contextualizing Migrant Mother as a moment within an expansive career, a new retrospective of Lange’s work has just opened at the Barbican in London. Titled Dorothea Lange: The Politics of Seeing, the exhibition traces the photographer’s work and legacy across multiple decades, articulating her working process through prints and archival materials, such as featured issues of LIFE magazine, first edition copies of breakthrough publications, and Lange’s own field notes and letters.

The exhibition begins with a selection of Lange’s pictorial portraits made throughout the 1920s. These images reflect her personal life in addition to the constructed narratives and characters she frequently associated with in the West Coast photography scene at the time. Commenting on the importance of this early work, Barbican curator Alona Pardo says, “We wanted to anchor and position her not only as this lone ranger doing her own thing, but also as someone who was very much in dialogue with photographers in the West Coast. It was important to do this before moving into her FSA photographs, which is of course the heart of her work.”

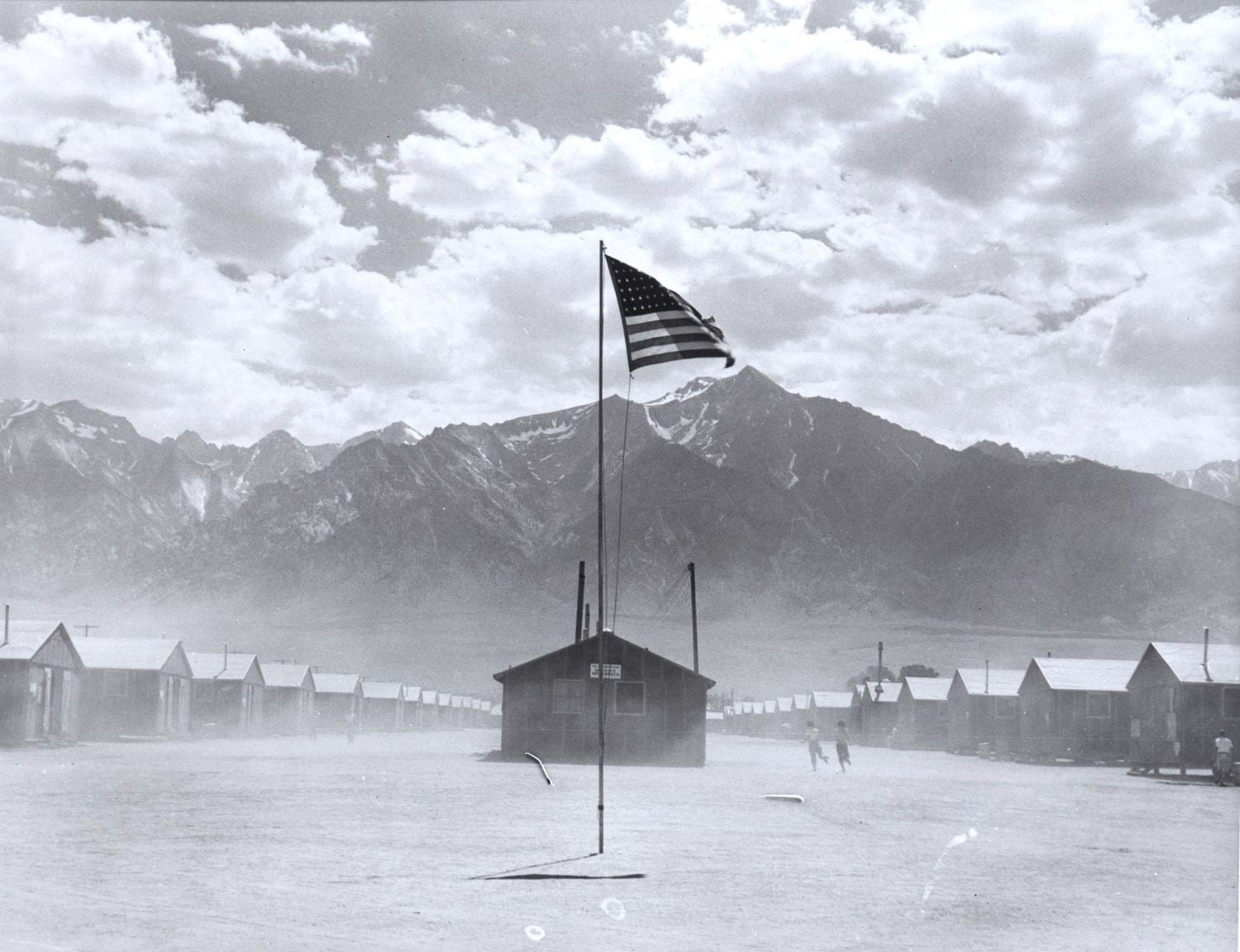

The FSA - or the Farm Security Administration - was a United States government agency created in 1937 to address the issue of rural poverty during the Great Depression. Lange was commissioned to document these repercussions photographically. The work she generated during that time, including Migrant Mother, is situated within the greater context of the Dust Bowl Migration, when 300,000 people migrated from the Midwestern Dust Bowl states to California in search of stable work.

Although Lange’s output during this period centers on the farmers who are vying for work, Pardo notes that the content has another focus: “It’s also about the politics of this time. What Dorothea is trying to get across in her work is the unfairness of social policy, which was not only hindering the white working class, but was also adversely affecting the African-American sharecroppers. She was commissioned by the FSA to take these photographs; she was not meant to be photographing American Filipinos or Mexican workers or African-American sharecroppers, but she does anyways. She was constantly going out and photographing the full spectrum of people on this migratory route.”

Considering how Americans and refugees continue to suffer from racialized mistreatment today, the current exhibition of Lange’s work feels particularly timely. “A lot of the welfare and social reforms prevalent today date back to the Depression era,” Pardo notes. “Dorothea was looking at the forced migration of people; they were escaping economic poverty because social and economic policies that negatively affected them were being passed by policy-makers who knew it would directly harm these people. We’re looking at the beginning of the capitalistic individual society, and understanding that lineage is important if we’re to contextualize what’s going on in America today.”

It’s important to note that Lange did not simply work to expose political injustice through images alone. Her method was more interdisciplinary, and the retrospective pays particular attention to her practice of blending images with text. “She was a trailblazing pioneer in her photographs, but her field notes also reveal how she championed an investigative approach to her work,” says Pardo. “She was interested in showing the greater context, working in storyboards. She understood how to tell the story that needed to be shown. She wasn’t an objective social documentarian in the vein of Walker Evans - she was doing the job within the framework of her own humanist philosophy on life. She understood that an image could speak louder than words, but she always anchored this image back to the individual’s own suffering - in their own words. There’s a lot of vernacular language that accompanies these captions, where she has transcribed, verbatim, what she has been told.”

Politics of Seeing follows a number of other recent socio-political photography exhibitions at the Barbican, including Another Kind of Life, which presented the work of numerous photographers from the 1950s to today, displaying narratives of counterculture, subcultures and minorities. Pardo posits photography as a particularly apt medium for bringing marginalized voices to the fore, and the exhibition of Lange’s work is a welcome chapter in this programming. She explains, “I often think photography is a reflection of the external world, and will therefore comment on and critique historical social discourses. As a public institution, we have a duty to raise public awareness of these issues. I think we need to give them a platform from which to represent a plurality of voices, experiences and realities that are sometimes combustible, and that look at the fragility of the world that we live in. We aren’t only trying to show Dorothea as a pioneering social documentarian - we are also raising awareness about the issues that she was photographing. She was principled and defiant and tireless in her pursuit of seeking justice, and I think we have a responsibility to show how that work is still relevant today. As an art institution, we don’t necessarily have a duty to educate, but we do have a duty to inform.”

© Dorothea Lange

This responsibility effortlessly parallels with Lange’s own impetus to expose the darker side of America, which is the main throughline coursing through the exhibition, reflected in each selected print and archival object as well as the title of the retrospective itself. “Dorothea felt that seeing the world was a political act. Photographing, for her, was always the politics of seeing. She was able to show, disseminate and circulate images of things that people weren’t seeing in their day-to-day lives, and she did everything she could to ensure they got into the media. The way she saw the world was through the framework of politics, and that visualization is what we are communicating with this exhibition.”

—Cat Lachowskyj

The exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is on view at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from June 22 - September 2, 2018 as a double bill alongside an exhibition of photographer Vanessa Winship’s poetic approach to documentary work.

We are delighted to note that Barbican curator Alona Pardo, interviewed here, is one of our jury members for the new LensCulture Art Photography Awards!