SpongeBob NoPants? Bizarre 'Nude' Sea Creature May Be a Sponge Relative After All

A "nude" sponge-like animal with no organs and just one orifice that lived 500,000 years ago is offering compelling new clues about a bizarre group of ancient creatures.

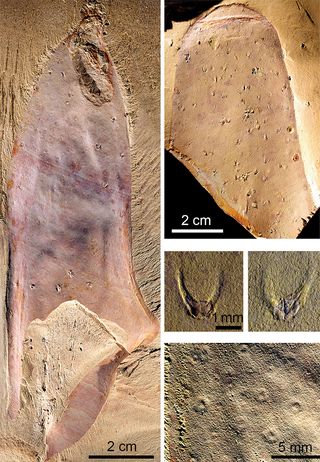

Though it somewhat resembles a sponge, the newcomer — now called Allonnia nuda — belonged to the now-extinct chancelloriids. Like sponges, they lived attached to the ocean bottom, and their bodies were generally covered with spines. However, this newfound species of chancelloriid was "naked," with spines that were much smaller and revealed more of the body surface than is typical for the group, researchers reported in a new study.

The findings suggest that chancelloriids followed a growth pattern similar to sponges and may have more in common with sponges than previously thought, study co-authors Peiyun Cong, a professor at Yunnan University in China, and Tom Harvey, a lecturer at the University of Leicester in the U.K., told Live Science in an email. [Cambrian Creatures Gallery: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

Tubular and spiky

Animals that lived during the Cambrian period half a billion years ago are known for being a little weird. During this time of explosive diversity, many bizarre forms emerged. There were enormous, shrimp-like predators; sea creatures encased in bladed armor; filament-covered comb jellies; and eyeless swimmers with figure-8-shaped bodies.

The researchers unearthed six fossil specimens of A. nuda from a site known for preserving a rich diversity of such Cambrian life — the Chengjiang site in Yunan province in southern China. The fossils had symmetrical, tubular bodies that were tapered toward the bottom and had an opening at the top; tiny, upward-pointing spines studded the creature's surface, and its single orifice was circled by a beard-like ring of spikes, the study authors reported.

Based on the biggest specimen, which was incomplete, the researchers determined that the creature could grow as long as about 20 inches (50 centimeters). This is much bigger than its fellow chancelloriids, which typically top out at 8 inches (20 cm) long, according to the study.

The scientsts soon found that the new species — and the chancelloriid group — had even more in common with sponges than prior studies had indicated. A. nuda's small, sparse spines offered an unprecedented view of the chancelloriid's body, emphasizing that their bodies, like sponges, were simple and hollow, with only a single opening, Cong and Harvey wrote in the email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But it also hinted at something else — a ring-shaped "growth zone" at one end of the animal, where all its new spines would emerge. This body growth pattern, only known in some modern sponges, would represent a biological feature shared only by sponges and chancelloriids, suggesting more complex similarities between the two than were previously described, Cong and Harvey said.

Evolutionary connections

Chancelloriids and other "Cambrian oddballs" — ancient animals from this period that don't fit neatly into the tree of life — can be puzzling to classify, but they also provide important clues about evolutionary relationships between animal groups, Cong and Harvey told Live Science in an email.

"The power of fossils is they show us direct evidence for animals that lived close in time to major transitions in evolution. It's a bit like a jigsaw puzzle, with the 'odd' fossils equally important, but just more difficult to fit into place," they said.

For example, two bizarre Cambrian creatures —Anomalocaris and Hallucigenia, which once seemed impossible to interpret — helped scientists to understand how arthropods evolved, "telling us about the early history of the group that today includes spiders, shrimps and beetles," Cong and Harvey said.

"In time, the hope is that groups such as chancelloriids will be similarly important in reconstructing the earlier stages of animal evolution, which is a rather more difficult prospect," they said.

The findings were published online today (June 19) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular