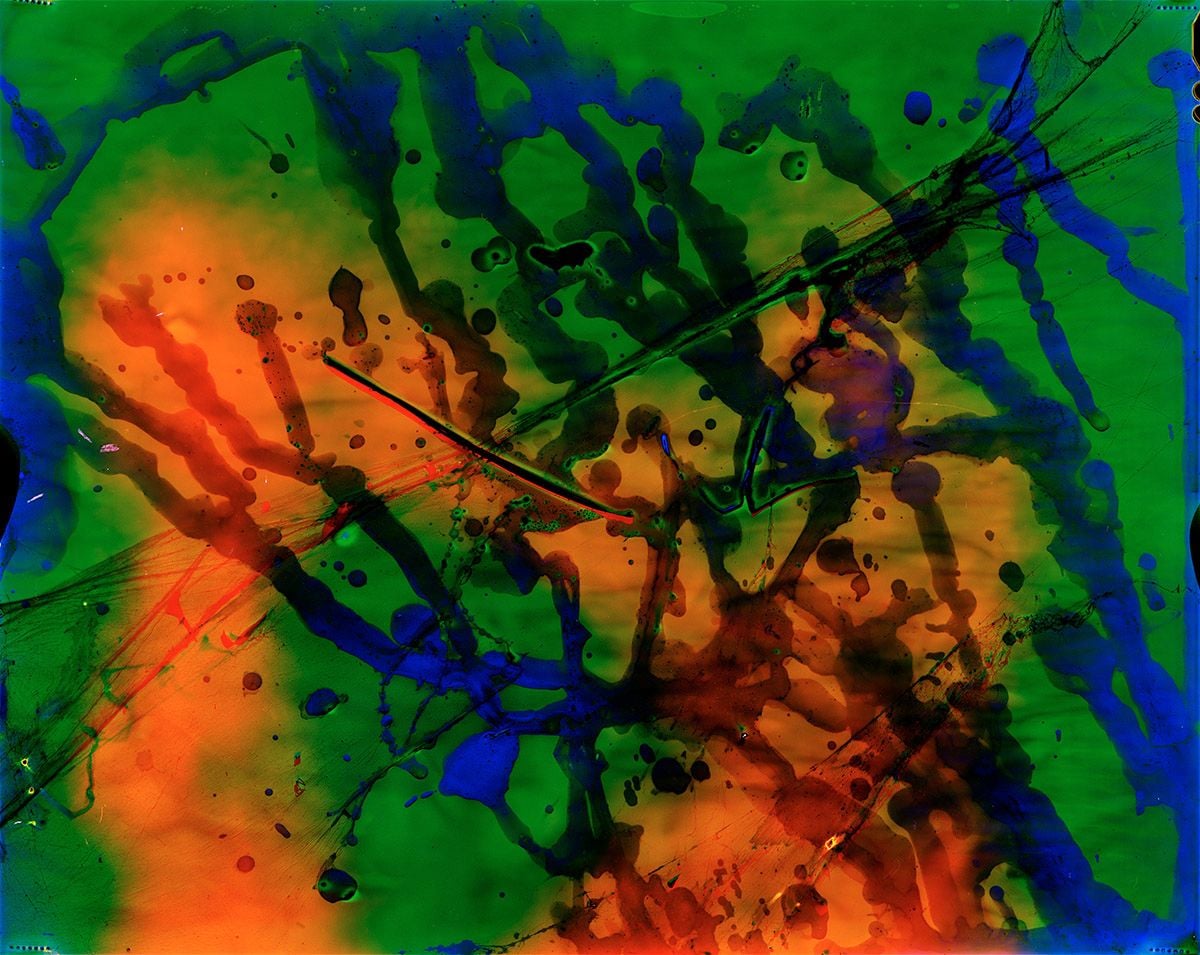

For over 40 years, Michael Flomen has been exhibiting his “photoworks,” many of which are produced using camera-less photo techniques that recall the earliest decades of photography, when pioneers like William Henry Fox Talbot were making the first photogenic drawings.

Today, Michael Flomen’s large-scale abstract phenomena photographs do not simply take nature as their subject, but rather reveal entire universes of events seen as microcosms. While Brassaï was fond of photographing Paris at night (especially the city’s cave-like graffiti), Flomen is Brassaï’s modern-day, backwoods counterpart, working the ecosystems of the world after dark. Unlike Brassaï, though, Flomen is willing to surrender control—the events of nature decide the outcome. In these photograms, nature itself becomes the found material, while the photographer is a kind of archaeologist of the instant who finds and reveals what is there.

As large-format photograms, Flomen’s camera-less photographs register the immediate physical conditions of light, rain, wind and life in their natural context. The results surprise us, bringing to mind macrocosmic views of immeasurable scale—the Milky Way, images beamed back by the Hubble Space Telescope. But this secret world is not light-years away: it’s a microcosmic one. The most minute movement of fish in a stream, or the dashing of insects through the air, comprise an integral part of Flomen’s process.

Flomen’s brilliance is in capturing the unpredictability of visible phenomena, bringing us in touch with the skin of the world. His talent is not in the usual photographer’s “mastery of the image,” but rather in how he reveals concealed, usually invisible moments, those wondrous phenomena that make up nature’s endless theatre.

—Alexander Strecker

John K. Grande: Michael, I have followed your work for some years. One of your best known photographs, “Double Trouble and Runner” (2001), involved the light patterns fireflies made by walking on your photo paper. The “Fallout” series (2011) was a response to the fallout from Fukushima. Your process and how you make photos without a camera is engaging, visually stimulating, and somewhat mysterious…

Michael Flomen: I work in all four seasons and with distinctly different organic materials in each one. Because each season provides different elements, for example snow or rain, my approach to making the picture varies throughout the year.

Some of my photograms are made by exposing large-format commercial films to the natural elements outdoors in the countryside. I have another series of pictures that are made from homemade negatives. I also make “shadow pictures” (to borrow the term coined by Tim Otto Roth), directly on light-sensitive paper.

JKG: Because of your process, do you have less control of how light and shadow will react than the usual photographer?

MF: I have as much control as I need. I have close to fifty years of experience with photographic materials. This has given me great familiarity with their limits. I’m looking for the accident, so in that sense I’m controlling my materials and the elements only up to a certain point. I want natural phenomena like wind and gravity to have an effect.

I’ve learned to work with white snowflakes on white photographic papers in near darkness. I may not see everything I should, but I trust the process. I trust that the vision I hold deep in my mind will ultimately be born.

JKG: Do your final prints ever show evidence of those unexpected variables?

MF: Unanticipated variables are major ingredients in my picture making. I embrace them. Every photograph I make teaches me something new and leads me to the next picture.

JKG: Your work process begins in analogue but also utilizes digital files for reproduction, and you have even started working on sculptural pieces rather than just two-dimensional images. Can you say more about these material distinctions?

MF: I am constantly trying to break rules in my art-making. In the past, some painters were keen on expanding painting. One thing that was restrictive to them was the traditional shape of the canvas. The same problem arises for me in terms of making photograms. Photography is still (largely) dealing with rectangular and square shapes. I have tried to get out of that rectangular format and to liberate the photograph.

Traditionally, the photograph was made in pristine environments where dust was the main enemy of the process. Any imperfection, even one ding in the paper, resulted in “failure.” After many decades printing in that environment, I decided I wanted to get “dirty.” Now my work celebrates all materials as an essential component of the work. Series like “X-Oids” and “Crunchtime” are made in part through the creative destruction of my negatives and photographic papers, all of which allow materiality to come to the forefront of the picture.

JKG: Is your environmentally sensitive process approach any different than, say, Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, and others who experimented with photograms nearly a century ago?

MF: In past, many people who made cameraless photographs made them inside the controlled atmosphere of the darkroom. For the last 20 years, my cameraless pictures have been made directly in the natural landscape, at night. So, yes, my approach is different. There is one pioneer of photography that worked in a similar manner: August Strindberg made his “Celestographs” on windowsills in the late 19th century. More recently, contemporary artist Susan Derges has brought light-sensitive photographic materials outdoors.

I consciously choose to work in collaboration with nature. For example, in the “Higher Ground” series, I partner with fireflies that mark the film with their bioluminescent light. I facilitate their direct participation so the bugs become equal actors in making the picture.

Furthermore, central to my process is my preparation for the creative act. My goal is to be receptive, with my senses heightened, so that I can be more attuned to my natural surroundings. My working experience involves listening, meditating, lying under the starry sky, breathing, and letting go of myself to become a part of the landscape. All of this activity manifests visually in the final photograms.

JKG: Artists like Floris Neusüss, Adam Fuss, Chris McCaw, and yourself work in an alternative strand of the medium that is intimately linked to place. What about your surroundings inspire you?

MF: I often work in the same areas in the countryside. I need to become familiar with the landscape in those places because I physically move around there under the cover of darkness. Then, because I am so aware of the environment I am working in, I notice the changes that the landscape endures due to weather and our effects on climate.

Photosensitive materials react to chemistry. Water in nature has become more acidic over time, mostly due to air pollution from human behaviour on the planet. Acidic waters include rain, snow, streams, lakes and rivers, not to mention the seas. These waters dissolve the surfaces of my materials. I use this effect as part of my mark-making on my photograms.

I work mostly in fresh waters. I have noticed the effects of global warming in the lakes and rivers that I frequent. Bryozoa and freshwater jellyfish seem to be on the rise, gradually appearing in the lakes I have been working in for years. Anyone who frequents a natural area knows and can see what is happening to that environment because of our impact on the planet. My work is increasingly documenting some of those effects.

JKG: A lot of art these days seems based on the dominance of “the concept,” without any sensory, spiritual, spatial or bodily relation to the environment. In contrast, your process is hands-on and owes a debt to permaculture, to the physical, tactile world the photographer works in and with…

MF: Well, it is said that artists make art in their own time. This work that I do is certainly of my time. Some world leaders and most environmental scientists say that humanity’s impact on the planet is the most pressing issue facing humanity today. Time is running out, according to them, to slow and reverse the effects that we have caused on our only planetary home.

My photograms measure a certain pulse in the natural landscape that is physical and spiritual. Our forefathers and mothers were well aware of our need to protect the land, living creatures and the spirit worlds. Most of us have lost those standards of living because we have lost contact with nature.

We need to be aware that the health of our environment is vital to our survival. Protecting water, air, and other life-sustaining elements is fundamental to our continued existence. I am concerned about the effects of climate change and global warming on the planet.

As long as I am making art, beauty and destruction will share the same picture plane.

—Michael Flomen, interviewed by John K. Grande

A world traveller from childhood, John K. Grande lived and studied in Sri Lanka, Norway, Switzerland, the UK, and Canada. His reviews, interviews, and features have been published in a range of magazines including British Journal of Photography, Arts Review, Artforum, la revue Espace, CIRCA, Vice Versa, Arte.Es, Sculpture Magazine, Public Art Review and Border Crossings. He has curated numerous exhibitions both in Canada and abroad.

Grande’s books include “Art, Space, Ecology,” (University of Chicago Press); “Balance: Art and Nature,” (Black Rose); “Intertwining: Landscape, Technology, Issues, Artists” (Black Rose); and “Art Nature Dialogues” (SUNY Press). See here for a full list of Grande’s publications.